From his album Another Green World (1975).

Category: Arts

Place de la République, Lille

John Singer Sargent: Lady Agnew

Alexey Shchusev: Hotel Moskva, Moscow

1972

John Burnet: Elgin Place Congregational Church, Glasgow

Bernardino Luini: Santa Caterina d’Alessandria

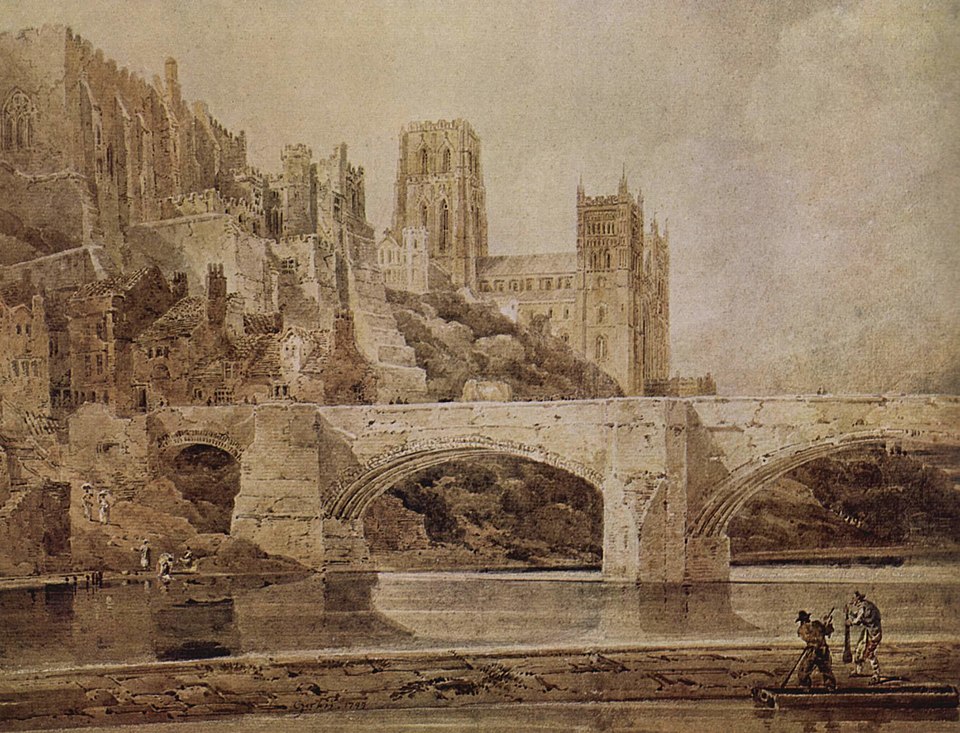

Thomas Girtin: Durham Cathedral and Bridge

Pink Floyd: Dogs

From their album Animals (1977).

Avenue du Midi, Bruxelles

Sedan 1948 Avenue de Stalingrad

Enrico Scuri: Selene ed Endimione