Maharishi Mahesh Yogi also speaks, at the beginning of this video.

Category: Spirituality

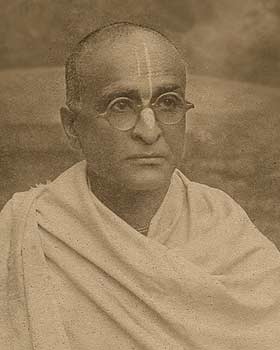

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Performs Guru Puja in his Last Days

–

“The task before Vedic India is to nullify the destructive forces of the British and American policies of NATO, by raising the nourishing Vedic influence in India and in world consciousness.”

Science of Being and Art of Living, Appendix A in the 2001 edition.

Note the non-hippie appearance of the Westerners in this video, which is characteristic of the transcendental meditation movement. Note also the absence of Indian bazaar kitsch.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: No Teacher of Hippies

–

“A general feeling has overtaken civilized society today that they should not infringe upon the feelings, likes, and dislikes of other people. This has gone so far as to create a widespread belief that even children should not be told what to do. It is said that they should not be told what is right and what is wrong, should not be guided to do good and to steer away from bad. This probably comes from the field of psychology, which brings out the principle of growth in freedom. But it is fundamentally unfortunate to let this criterion of freedom overshadow all the basic fundamentals of advancement of life. If one does not know that the thing that he is doing is going to harm him either now or later, then someone who has that knowledge must tell him, in a spirit of love, kindness, sympathy, and help, that this action is not right.

If a child is going to pick up a burning coal, thinking that it is a lovely bright toy kept there for him to enjoy, it is only right for the parents to stop the child from going to it, even if the child resents not being permited to jump into the fire. Such a freedom is ridiculous and dangerous to the development of man, to the development of the younger generation, and to the development of the innocent, ignorant people who do not have this wisdom and the experience of life. It is the responsibility of the elderly people to advise the young. Even if the young people resent their directions and do not obey, it is good to tell them. They will find out for themselves the result of not obeying their elders, but if the elders do not speak out at all and leave the child to find out for himself that it was wrong, then they have wasted the child’s time and have been cruel to him. Knowing that it was not right for the child and not helpful for his life, they did not keep him from going that way. it is a very wrong tendency in parents to believe that whatever they say must be followed by the child, but if they see the possibility of the child resenting their advice they keep quiet and do not give it. it is not kindness; it is not live; it is not right for the parents to take this attitude. The child is young and inexperienced and has not that broad vision and experience of life. In all freedom for the child, the parents should tell him in love and kindness that this is wrong and that is right. If he resents it, the parent should not much insist, because if he does not obey and does that thing, he is naturally going to come across an experience which will tell him that his father or mother was right. That is the way to cultivate the tendency of the child to obey and act according to the wishes and feelings of the parents. If the child is resentful and does not obey, the parents have at least done their duty in informing the child. And then again, it is also their duty to have the child informed of the right action by their friends, teachers, and neighbors – from someone whom the child really loves and obeys. It is the duty of the parents to see that the child is brought up on all levels of wisdom and good in life. The responsibility for not having told the child what is right and wrong and not trying to change his ways if he is going wrong lies with the parents. Children are the flowers in the garden of God, and they have to be nourished. They themselves do not know which way is better for them to go. It is for the parents to make a way for them that is free from suffering. It is also part of the parents’ role to punish a child if he does not obey and does wrong, but the children should be punished in all love.

It is the foremost duty of parents to see that their children are brought up on a constructive scale of wisdom and right action in the society. And the modern tendency of putting the fate of the children completely in their own hands is highly detrimental. It only leads to uncultured growth of the younger generation.

There are schools in some countries which advocate complete freedom for children, but these schools are basically the result of a policy sponsored by those whose sole purpose is to make the nation weak and who therefore want the younger generation to grow up without traditions and without any cultured basis in life, devoid of the strength of character. It is cruel and greatly damanging to the interests of human society not to guide and shape the manner of behavior, thinking, and action of the younger generation through simultaneous love and discipline. The same idea has crept up even in the schools for very young children where the teachers are forbidden to punish the children. The result is found in the growth of child delinquency, leading to juvenile delinquency and to great uncertainty in the minds of youngsters about the right and wrong of an action, thought, or mode of behavior. Today’s youth does not understand and does not have any comprehension of the standards of traditional decent behavior of his nation. This is just the wild growth of undeveloped minds without the background of any traditional culture.

It is a shame that education in many countries has been influenced in such a manner, in the name of growth in freedom. There have been disastrous results from not shaping and directing the modes of thinking and behavior in the lives of the younger generation.

It is up to the statesmen, the patriots, and the intelligent people of the various nations to look into the disastrous results of such a pattern of education, perperated in the name of child psychology, and to amend the ways of education and the raising of the children. Children should be loved and they should be punished. They have to be loved for the growth of their life, and they have to be punished if they are wrong. This is just to help them to succeed in life on all levels. Each nation has a tradition of its own, and its people have their religions and faiths. The children should be given the understanding of their tradition, their religion, and their faith.

It is a great mistake on the part of educators today to find an excuse in the name of democracy not to give any traditional understanding to the children. Such ideas necessarily originate with those whose motive is to weaken the nation and rob the people of their national traditions and dignity. And to root out the traditions of the society is the greatest damage that can be done to the welfare of a nation. A society without tradition has no basic stability or strengh of its own; it is like a leaf left to the mercy of the wind, drifting in any direction without any stability and basis of its own.

In the name of modern education, the societies of may countries are drifiting away from old tradition. The result is a wild growth of faithless people, without tradition, whose society exists only on the superficial gross level of life.”

Science of Being and Art of Living, 1963 (2001), 225-8.

Note the absence of Indian bazaar kitsch in this video.

Bhaktivinoda Thakura

John of Salisbury

Ruysbroeck

Paul Brunton

This is another lastingly important vartma-pradarshaka guru (person who shows the path) from the late 1970s. He wrote well; his books from the 1930s and 40s have a pleasantly traditional, sometimes almost idealistic Victorian style, a not quite contemporary style, even as he discussed, for instance, new and distinctively twentieth-century developments. This style was eminently suited to his substantial purpose of introducing Eastern spirituality and metaphysics. (It must be added, however, that something of this style almost of necessity has to be preserved in all truly spiritual writing, and that it indeed is to some extent preserved also in later Western spiritual writers, even though it is in them strongly attenuated. It is striking that this interesting subject of the literary style of such writers, introducing Eastern spiritual doctrines, seems not yet to have been explored at all. The change in style from nineteenth-century more or less idealistic comparativists and newly Eastern-oriented esotericists to the traditionalist school and the New Agers should be an interesting and revealing field of study.) Only in his most philosophical books does he, at times, become somewhat too repetitive. René Guénon wrote relatively favourable reviews of two of his early books.

William Law

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

There is much criticism of Maharishi. If we disregard the perhaps somewhat one-sided understanding of vedanta, there are also some adaptations to modern western mentality that can certainly be questioned.

There is much criticism of Maharishi. If we disregard the perhaps somewhat one-sided understanding of vedanta, there are also some adaptations to modern western mentality that can certainly be questioned.

His charging money for his TM-courses, his selling meditation as a mere technique, of course disqualifies him in orthodox “Hindu” circles and among many others. Maybe he shared Rajneesh/Osho’s discovery that for most westerners, that which costs nothing seems to be worth nothing, and that a price is therefore necessary to to make meditation sufficiently attractive; that people want to pay, and pay much, in order to enjoy a feeling of being special by thus gaining access to something rare and exclusive. His marketing by means of mystical powers, siddhis, making possible so-called “yogic flying”, appears obviously over-the-top and fraudulent, even though I understand the point was not the flying itself but the coherence between transcendental consciousness and bodily function that it advanced and signified. It seems to be in stark opposition to the line taken with regard to siddhis of almost all other teachers in the tradition (and indeed also western esotericists), even those who made other adaptations in spreading their teaching in the west. Many formulations in his books are too vague. It is understandable that his view of a current “age of enlightenment” and his idea of a TM-based “government” of nations and the world are viewed as problematic. And his parallels between the vedas and contemporary science can certainly appear to be unduly speculative.

Most centrally, I don’t think – and it isn’t my experience – that transcendental consciousness (turiya, samadhi) is so easily, naturally and quickly reached by his meditation technique as he says it is. He in fact seems to simplify the spiritual practice and its description so much that in reality he might make the process of realization harder.

It is quite as striking in Maharishi as in Vivekananda and his followers, and indeed in all major sophic texts in “Hinduism”, older and newer, how the elements of sankhya, yoga, karma-mimamsa and vedanta are all present and drawn on in his teaching and commentary. They seem almost always, and increasingly in modern times, to appear together, variously combined in the individual sub-traditions, schools, and gurus or swamis. Maharishi even holds that a full understanding of the Bhagavad-Gita is possible only through a combined elucidation by separate commentaries written from the perspectives of all of the six darshanas.

Vivekananda’s conception of what he calls “the yogas” (jnana yoga, bhakti yoga, karma yoga and raja yoga) adds further confusion. And then there is hatha yoga, kundalini yoga, laya yoga, kriya yoga, maha yoga… – all partly, and unclearly, related to Vivekananda’s categories. It never ends. There were always other forms of yoga in addition to Patanjali’s ashtanga yoga, which is seemingly identical with raja yoga. And countless variations of teachings of centres, energies, currents, lines, channels, airs, humours, luminous orbs and colourful circles and wheels and points and stars inside the body, “traditional sciences” in all areas (medicine, architecture etc.), worship of images, stones and plants, and innumerable little folk-superstitions of all kinds. For a long time, most of it was also inextricably intervolved with Buddhism. And, not least, and perhaps most fundamentally, everything in this compact whole is mixed up with the endless and ever-changing mythological stuff and a never-ceasing flood of new avatars (nowadays only in human form, I think). An unfathomable chaos. A tangle. A mess. It cannot be sorted out.

Fortunately, it doesn’t have to be sorted out. In addition to being impossible (not just all rational-empiricist scientific questioning with regard to this totality, but all genuinely philosophical, is finally met with a wall of a kind of incomprehension, and everything is just carried on in what can look like blind faith), that is in fact both unimportant and uninteresting. One “only” needs to discern and ascertain what is true and real. Most of those important components are present in undifferentiated seed form in the classical texts, and not at all organized in accordance with the later, seemingly never strictly maintained or upheld distinctions and divisions.

As for yoga, Maharishi’s understanding of it (in the sense of the practice of ashtanga yoga, not that part which, as a darshana, it shares with sankhya) is that it starts with samadhi, and that perfection in all the other limbs is achieved through its prior attainment. The mantra meditation, leading to transcendental consciousness, the goal of the act of meditation itself, for which the mantra is merely a means, is to be supplemented by a natural life and activity in ordinary, waking consciousness which infuses transcendental consciousness into it, so that these states finally coexist permanently in what Maharishi, using Richard Maurice Bucke’s term, translates as “cosmic consciousness”, which, in turn, culminates in full God consciousness.

What Maharishi’s technique of quiet, inner focus on short bija mantras does is certainly to take us closer to transcendental consciousness (that is of course always there – and here – and what we already really are, not in itself in need of any “realization”). It is, it seems, primarily a form of dharana, which can be developed into dhyana. What is definitely reached, and indeed easily, naturally and quickly, is subtler levels of the mind. This not only leads us in the direction of samadhi, but also, as Maharishi emphasizes, in itself sharpens the mind, makes it clearer, increases its conscious capacity and range of perception.

But in my view, much more needs to be said about meditation, in line with how ashtanga yoga has traditionally been taught, i.e., the other seven limbs too need to be separately focused on to a greater extent – not least since, again, Maharishi’s transcendental meditation is, primarily and initially, a form of two of them, not of attained samadhi. It does seem clear that the partial goals of the other angas are indeed reached through samadhi as realized through Maharishi’s form of meditation. But if it isn’t thus realized, or before it is thus realized, it is difficult to see why the other angas and their special practices should be ignored. Of course, yama and niyama are for the purification of the mind and the development of character that are needed even in order to acquire the motivation to practice yoga in the full sense. Asana and pranayama, it seems to me, may or may not be necessary or helpful, depending on the individual character and nature of the practitioner. But as for the higher limbs, it isn’t easy to see (at least not for me, but that may be because of my strong sensual attachments and general lack of spiritual advancement) how dharana, and therefore also dhyana, can normally be practiced with success without prior accomplishment in pratyahara, the interiorizing withdrawal of the senses and the mind from the objects of the senses, which, at least in the west, seems to be a much neglected and probably misunderstood anga. But it should certainly be accepted that such practice, without them, is in principle possible with Maharishi’s technique. When what Maharishi calls cosmic consciousness is attained, and then, of course, God consciousness, pratyahara (and interiorization in general) is clearly not needed, but it helps in overcoming attachment to the objects of the senses on lower levels.

What must also be taught however – and Maharishi does speak about it in the chapter ‘Intellectual Path to God Realization’ in his book Science of Being and Art of Living – is that even the complete practice of ashtanga yoga isn’t the only method of spiritual development and self-realization: there is also the purely intellective path of jnana, with its discrimination (viveka) and concentration of the consciousness or awareness which is always already there, that in which our whole being and experience already rests, and which only needs to be purified and liberated from the various layers of mental and sensual content. Elsewhere, it seems Maharishi does perhaps not stress this enough, relying instead on sankhya only even when he speaks of jnana, and on the related yoga only as the practice of realization. The jnana and spiritual realization of vedanta goes beyond the goal of yoga.

Transcendental consciousness isn’t, it seems, in its basic nature radically different from and other than waking consciousness. It is just that, covered by ignorance, the veiling of delusion, we can’t appreciate its true and full nature. Indeed, the consciousness in which we experience our “ordinary” self and its “ordinary” world is in itself strictly the same as that of the most elevated, transcendent “mystical” experience, of the highest God consciousness. This only needs to be realized, and this realization is attainable also without the process of bija mantra meditation. The mantra is only a means, allowing consciousness to reach subtler levels of the mind and ultimately to transcend both the mantra and the mind with its contents with the help of it. The process is one of the awareness or the con-sciousness that is always already there in ordinary perception and in the attention to the mantra; it is about the awareness or the consciousness that is already there, but as gradually elevated from its ordinary level of sensual entanglement. More precisely, it is about on the one hand what I think should be the right referent of William James’s term sciousness, consciousness con nothing, in itself, as transcendental, without phenomenal contents, and the process leading to it. But, since samadhi isn’t reducible to that pure sciousness, it is also about how it exists, preserved through the practice of meditation, in its transcendental purity along with its contents in the form of the phenomenal manifestation of the “cosmos” on a new and altogether higher and subtler level, as “cosmic consciousness”; and ultimately as the God-consciousness of the oneness of all in God. It is what is always already there and real that, as it were, needs to be realized. And this can be done also without yoga and mantra meditation, by means of the vedantic insight that Maharishi also strongly affirms. But the practice of more than one spiritual technique or discipline can of course be beneficial and helpful.

Maharishi is typical of the gurus and swamis who took the spiritual practices of the vedic tradition to the west in that he deemphasized the mythological legacy of the vedas, the upanishads, the itihasas and puranas so much that it is almost wholly absent in his books and other presentations. This is a correct approach, one of the fruits of, on the one hand, the thousands of years of patient, systematic interpretation, exegesis and refinement of the teachings of the vedic tradition, and on the other of the insights into the necessity of a certain adjustment of their presentation to the cultural and intellectual specificities of time and space.

His advaitic tradition does, in itself, retain the legacy in its own way, either as representing realities on a lower level, in the phenomenal manifestation, the world of illusion, and/or – it seems to me – as something that isn’t necessarily accepted and never even intended to be necessarily accepted as literally true. It isn’t wholly absent in Maharishi. Although they are only very few, residues of the unquestioned literalist outlook of tradition are found in his understanding of the history of the universe, the succession and cycles of the yugas, and the dates of authorities like Vyasa, Adi Shankara, and indeed, although less unambiguously, Krishna himself.

Sri Aurobindo is known to have grappled with the issues raised by the evolutionism of modern science, and I suppose many other intra-traditional scholars must have done so too. But it is remarkable that the disciplined minds of vedantic exegesis haven’t reached any kind of consensus or made up their minds with regard to how these questions are to be addressed, so that to this day it is possible for vedanta and yoga teachers to simply restate the traditional accounts as they are, without any kind of explanation or commentary, to simply present them as literally true. Attempts to defend the literalist understandings in explicit polemics against modern science, even seeking to refute it using its own assumptions, accepting its empiricist methodology, are rare, although they can be found in the branch of “Hinduism” that are based precisely on the literalist acceptance of the mythological legacy, such as Vaishnavism, as that tradition has been taken to the west.

Maharishi presents no direct challenge of this kind, but there is at the very least an indirect one in his mere unquestioned restating of the view of the yugas on pp. 253-55 of his commentaray of the Bhagavad-Gita. It should be noted that, also quite independently of modern science, there is, as with regard to the combinations and the coordination of the various components of the amorphous, chaotic and starkly contradictory mythological legacy in general, in reality no consensus on this teaching within the tradition itself: Sri Yukteswar, the guru of Paramahamsa Yogananda, for instance, held a completely different view of the order of the succession of yugas and of which yuga we now live in than that found among others authorities. But the assertion of any version of this teaching about the age and history of the universe and humanity of course starkly contradicts the scientific findings regarding the history of man, the life on earth, the geological time scale, etc. Readers with even just the most superficial familiarity with science will unfortunately be inclined to reject much or all of the other teachings when they encounter such passages.

An example of relatively serious criticism of Maharishi (and also of Aurobindo and Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh/Osho) can be found in a lecture by Rama Coomaraswamy. Yet it is also poorly written and somewhat simplistic, and Coomaraswamy’s endorsement of the more superficial and strained version of the Guénonian, perennialist-traditionalist interpretations of Catholicism (and indeed Christianity in general), and his consequent, largely failed personal engagement as a Catholic, in my view in important respects disqualifies him too as a critic. He neither speaks as a strict “Hindu” traditionalist, nor does he address the complex issues regarding the specific difficulties of spreading anything of vedic spirituality in the modern west, or the partial compromises and adaptations which many found to be necessary because of them. These decisive weaknesses are the same as those that, unfortunately, vitiate the otherwise in some respects important criticism of writers like Lee Penn (False Dawn: The United Religions Initiative, Globalism, and the Quest for a One-World Religion (2005)).

Then, as in the case of almost all Eastern spiritual teachers in the west, there is also criticism of Maharishi’s personal life. Almost all are accused of sexual abuse of their followers. In some cases, including Maharishis, it is perhaps not so much a case of accusations of sexual abuse, but, as it were, merely of use. But none of this is something I can judge about. Some of it is probably true. In cases where, if so, it contradicts their teaching or their claims, it is clearly serious. But it is probably also the case that some accusations are false, and produced for other reasons and because of psychological disturbances and characterological flaws of those followers. But these questions can and should, I suggest, be distinguished from the substance of the teachings themselves, quite apart from what is true about the individual teachers.

In reality, despite my own remarks above, Maharishi’s commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita is in some respects an “original” contribution, in the sense in which originality must always be understood within a general traditional framework, i.e. in terms of original claims regarding traditional meanings lost or obscured by other commentators and interpreters. As far as I can see, it has been generally underrated as a result of the mentioned, legitimate criticisms. Indeed, the critics never seem to have studied Maharishi’s interpretation of the first six chapters of the Bhagavad-Gita closely. Not all formulations are too vague; in fact, his account of the process of meditation in all aspects is often very precise. I find that in important respects the interpretation actually marks a step forward in the gradual, new transmission of the vedic tradition to the west which has been going on since the late 18th century. Given the particular, unavoidable difficulties of this transmission, a similar attitude should be taken to Maharishi’s work as to the whole of the so-called neo-vedantist current, and indeed, mutatis mutandis, to modern western New Ageism. Discernment, not wholesale acceptance or rejection, is what is called for. The historical importance of these currents for the spread of the vedic tradition in the west cannot be denied, even as proper attention is brought to their errors and incompleteness.

With regard to western adaptations in his interpretations of his own tradition, it isn’t clear that there is more of them in Maharishi than in Vivekananda and the Ramakrishna mission, in Aurobindo, or in other, earlier transmitters of the vedic tradition to the west. And such adaptations are indeed necessary and in many cases even desirable. Moreover, his teachings are sharply at odds with the still further developed romanticism of the hippiedom which shaped the west at the time when he spread them here – a fact that was obscured by the fact that hippies, and the Beatles, were attracted by and came to be associated with him.

It also seems to be a fact that very few are in reality capable of practicing regularly his adapted form of meditation, even as they dismiss it as unduly simplified. As long as this is so, there can be no doubt that they have much to learn from him. I was initiated into Maharishi’s practice of transcendental meditation by his student, now Professor Bengt Gustavsson, at the TM centre in a beautiful building from the 1880s or 1890s in Skeppargatan in Stockholm, in 1978. I find it important that I sensed deeply the spiritual purity, peace, and power of those rooms on that occasion, and of the beautiful ceremony, with the flowers, fruit, and white handkerchief I had been told to bring, the pictures of Maharishi and Brahmananda Saraswati, the incense, etc., and the mantras Gustavsson recited. On this occasion, transcendental meditation was certainly not just a technique, although it was that too and was, above all, marketed as such; it was very definitely also a distinct initiation into Maharishi’s branch of the vedic tradition. Moreover, there was no trace of either Indian bazaar kitsch or countercultural hippie aesthetics. Gustavsson always wore a suit and tie.

The practice immediately led to experiences described in Gustavsson’s introductory teaching and in Maharishi’s books and other literature on TM. Since then, I have also studied other branches of the vedic tradition and practiced other forms of meditation etc., but I still find Maharishi’s transcendental meditation, understood in terms of his own scriptural commentary, to be of considerable importance. He, and Gustavsson, remain more than just vartma-pradarshaka gurus (gurus who show the path) in the sense that, to this day, Gustavsson’s initiation remains my only formal “initiation” (of course not accepted as such by “Hindu” traditionalists) in the vedic tradition, although I have subsequently had closer association with other teachers. Although I have alternated and supplemented with other techniques, in terms of initiation and practice, this is basically where I still remain. And it is where I think I ought to remain. Non-adapted forms of vedic spirituality seem to me in many ways problematic in the west.