Personal “Reason” and Impersonal “Understanding”

Personal Unity-In-Diversity

Bowne, the paradigm of personalism according to Knudson, sometimes seems to swerve from the strict polar extreme of Knudson’s classification and to employ an idealistic language purer even than that of the British personal idealists and closer to that of the speculative theists. In a sense, Bowne is emphatic about voluntaristic creationism. [1] Existing in relations is not precluded by the concept of the absolute if the absolute freely posits the relations and they are ‘not forced upon it from without’; ‘the world depends upon the divine will’, which is free from the limitations of human will; ‘the world of spirits must be understood as created’; ‘It is not made out of preëxistent stuff but caused to be’; ‘Creation means to posit something in existence which, apart from the creative act, would not be.’ [2] With classical theism, personal idealism makes creation a free, voluntary, divine act, distinguishes between the creator and his works, and conceives of the latter ‘as having a certain objectivity or otherness as over against its Maker’. It rejects emanation theories that reduce the world to ‘a part of God or a necessary consequence of the divine nature’ and ‘practically identify the world with God’. [3]

Yet against classical theism, Bowne’s personalism holds that the external, created, ‘material’ world is not metaphysically real, but ‘a phenomenal order maintained by a divine or at least a spiritual causality. In and of itself nature has no independent reality.’ While things are not reducible to our perceptions but independent of our consciousness of them, Knudson still thinks that ‘[t]he theory that things are divine thoughts may help us to understand how we can know them’. The world may be said to be God’s thought, but if so, it is God’s thought ‘objectified…by the divine will so as to be in sense an “other” to God’. [4]

Elsewhere, Bowne in fact also expresses himself with considerable caution on the question of the origin of the finite beings from the absolute. The possibility of their ‘community in unity’, he admits with the same un-Hegelian self-restraint as Grubbe, ‘is one of the deepest mysteries of speculation’. He seems to accept that an ethical God ‘must have his adequate Other and Companion’. The question is then whether, and/or in what sense, the ‘eternal generation’ or ‘necessary creation’ of that Other is for this reason required. [5] Love, justice, and benevolence all require for their meaning a plurality of persons. ‘Love would have no meaning in a world where mutual influence is impossible’. [6] On his own, God is ‘only potentially a moral being’, who needs an ‘adequate object’ in order to ‘pass to adequate moral existence’. The pantheistic view of the eternal generation of a plurality of ‘others’ within the divine unity, as ‘essential implications’ of himself, dependent on the divine nature and not on the divine will, numerically distinct but ‘organically and essentially one’ with God – the view held, with a certain interpretation of their teaching of the idea of the finite beings in the mind of God, by more or less absolutist personalists like Grubbe and Boström – could of course not, on Bowne’s premises, be rejected because of the merely formal opposition of unity and plurality. But at the same time, it is impossible on the same premises to ‘carry the actual world of finite things into God without speculative disaster’. In this situation, Bowne concludes that the only alternatives are to abandon perpetual, necessary creation or accept, ‘apart from the finite system’, persons coexisting as ‘coeternal with God himself’. Such speculation may help ‘forward the thought’, but its ‘best expression’ has not yet been reached. He mentions that Trinitarianism may for some have solved this problem without the world becoming necessary for ‘God’s self-realization’, but then interrupts the treatment of the subject by saying that he has ‘no call to enter’ into it. [7] Like the passages on the divine thoughts cited above, this one seems to me to be an important proviso, which keeps his voluntaristic creationism with regard to finite spirits and their world clearly within the tradition of idealistic speculative theism. But to return to my main point here, this does not detract from the distinct personalism of his position.

Of course, the relation between the many and the one, understood as the finite spirits and the absolute spirit, cannot for Bowne be solved by any quantitative conception; the many do not result ‘from any fission or self-diremption of the one’, they are not ‘made out of the one’, or ‘included in the one, as the parts are included in the whole’. Such conceptions are made impossible by insight into the nature of the unity of the one: ‘Metaphysics shows that the fundamental reality must be conceived not as an extended stuff, but as an agent to which the notion of divisibility has no application…as self-conscious intelligence’; ‘For the explanation of the world we need an agent, not a substance’. [8]

Quantitative substantialism being perceived as an uncritically imaginative picturing of the unpicturable, and the dangers of this kind of thinking being evident ‘in the Vedanta philosophy of India’ (by which Bowne means Shankarite advaita vedanta), have, however, forced many thinkers to take refuge in the opposite extreme of ‘an impossible pluralism’ (Bowne would have had in mind James, and perhaps McTaggart and even Howison [9]). It is only transcendental empiricism that will here help us steer clear of the Schylla of such pluralism without falling back on the Charybdis of pantheism. Critical consideration of our life yields two facts. First, ‘we have thoughts and feelings and volitions which are inalienably our own’, ‘a measure of self-control, or the power of self-direction…a certain selfhood and a relative independence. This fact constitutes our personality’. Second, ‘we cannot regard ourselves as self-sufficient and independent in any absolute sense’. These two facts are basic experiential givens, and contradictory only if taken abstractly. Denial of any of them ‘lands us in…nonsense’. [10]

Such we find ourselves given in experience, and this fact is to be accounted for, not explained away. ‘Causes are revealed in their deeds only’, and the philosophical question is what we can know of the ‘invisible power’ which thus produces us and the phenomenal order. The whole world of ‘space appearance’ and physical science is ‘not a self-sufficient something by itself’, but a means of symbolizing, expressing, manifesting, and localizing, of the deeper, underlying personal life which is the ‘only substantial fact’. Our own visible appearance in the space-world, our physical organism, is just ‘a means of expressing our hidden thought and life’, of ‘manifesting our inner life’, our unseen ‘living self’. They key and meaning of physical attitudes and movements are found only in the invisible, personal world behind them which alone give them human significance. Here lies ‘[t]he secret of beauty and value’. Everyday life, no less than literature, history, government, society, are in reality relations of ‘personal wills…with their background of conscious affection, ideas, and purposes’. ‘[C]onsciousness…is the seat of the great human drama’. [11] In these formulations, insights best known perhaps in the form of Dilthey’s hermeneutics are restated in terms of personalism and in support of it.

Once we realize these truths, we also begin to be able to conceive of the whole of the space-time world as a similar means of ‘expressing and communicating’ the purpose of ‘a great invisible power’ behind it: ‘A world of persons with a Supreme Person at the head is the conception to which we come…The world of space objects which we call nature is no substantial existence by itself, and still less a self-running system apart from intelligence, but only the flowing expression and means of commmunication of those personal beings.’ [12]

As we have seen in Chapter 1, since for Bowne, ‘we are in a personal world from the start’, and since ‘all our objects are connected with this world in one indivisible system’, in a sense this world of persons is also the starting-point of his philosophy. Even if other persons are given as data of experience, it seems insufficient to say that he starts merely from the data of self-consciousness; the explicit point of departure of his philosophy is rather ‘the coexistence of persons’, the personal unity-in-diversity: ‘It is a personal and social world in which we live, and with which all speculation must begin. We and the neighbors are facts which cannot be questioned.’ The persons of this social world are bound by ‘a law of reason valid for all’ as a condition of their ‘mental community’, and they have ‘a world of common experience, actual and possible’, where they ‘meet in mutual understanding’. [13]

It is this personal world, with phenomena as the expressions of personal wills, that is the only motive of creation. Since transcendent completion – identical for Bowne with the absoluteness of the absolute – is strictly maintained, this motive can be no ‘lack or imperfection’ in God. Only our ‘moral and religious nature’ can give us an idea of the true motive, although creation cannot be ‘deduced’ from ethical love, since we cannot a priori ‘fix’ the ‘implications’ of the latter; it can only be a matter of faith. This sounds like a slightly more sceptical position than that of the European personalists. Yet at the same time, Bowne insists that ‘[a] community of moral persons, obeying moral law and enjoying moral blessedness, is the only end that could excuse creation and make it worth while.’ [14]

In his introductory discussion of Comte in Personalism, where Bowne accepted Comte’s description of the historical change from the ‘personal’, theological stage to metaphysical explanations in history, he holds that Comte was wrong in his description of the nature of personal explanation, in making ‘caprice and arbitrariness the essential marks of will’ and in rejecting causal inquiry. Bowne refuses to accept the historical succession of abstract metaphysics and positivism as progress, and insists instead that what is needed is the adequate philosophical exposition of the nature of the personal explanation. Bowne aims to show that

[Block quotation:] critical reflection brings us back again to the personal metaphysics which Comte rejected. We agree with him that abstract and impersonal metaphysics is a mirage of formal ideas, and even largely of words, which begin, continue, and end in abstraction and confusion. Causal explanation must be in terms of personality, or it must vanish altogether. Thus we return to the theological stage, but we do so with a difference. At last we have learned the lesson of law, and we now see that law and will must be united in our thought of the world. [15]

In personalism, the principle of the – in one sense – ‘pre-rational’ worldview is thus retrieved within the rational project of philosophy.

The ‘meaning of causality’ is revealed only ‘in the self-conscious causality of free intelligence’ and the concomitant certitude of its actuality. Indeed, it is the only causality of which we have concrete experience and knowledge, ‘and the only causality which really explains’. Other conceptions of causality are inherently inconsistent. The true cause, Bowne seeks to show, is ‘immanent throughout the series’ of phenomena, ‘as the living power by which all things exist and all events come to pass’; it cannot be ‘sought at the unattainable beginning of an infinite series’. In reality, other causal explanations are merely a matter of ‘superficial classification’ of the interrelation of phenomena. Volitional causality means ‘dynamic determination’, in contradistinction to the mere logical determination typical of a certain kind of rationalist systems. Based on logical determination, from premises to conclusions, such systems cannot accommodate dynamics, and seeking to ‘construct a theory of intelligence without including the will’, they must rule it out. In reality, will is an integral and essential part of intellect; more consistently than other personalists, Bowne not only insists on the original personalist intuition that onesided rationalism – or more precisely, in his view, misconceived rationalism – in fact leads to its opposite, but goes so far as to write that intellect, ‘conceived simply as a logical mechanism of ideas, is something that is totally incompatible with rational thought, and lands us in the midst of antinomies worse than those of the Kantian system’. [16]

Volitional cauality cannot be construed in its possibility; because of its fundamental charcter, the very question of possibility is irrational – all accounts of possibility requires such a basal given. This, again, is Bowne’s ‘transcendental empiricism’:

[Block quotation:] Intellect explains everything but itself. It exhibits other things as its own products and as exemplifying its own principles; but it never explains itself. It knows itself in living and only in living, but it is never to be explained by anything, being itself the only principle of explanation. When we attempt to explain it by anything else, or even by its own principles, we fall down to the plane of mechanism again, and reason and explanation disappear together. But when we make active intelligence the basal fact, all other facts become luminous and comprehensible, at least in their possibility, and intelligence knows itself as their source and explanation. [17]

Like causality, potentiality is merely a ‘term of the understanding’, an ‘abstraction without any real content’, a ‘formal principle that float[s] in the air’ apart from a concrete experienced reality which gives it an intelligible meaning. This can never be found ‘on the plane of necessity and impersonal causation’, where it must be ‘at once real and not real, actual and not actual’, but only on that of personality: the free agent’s self-determination is a choice between different ‘possibilities’ which may also be called ‘potentialities’. The concept of potentiality can only explain that which it has historically been used to explain, namely ‘motion, progress, development, evolution’, if these are conceived, by analogy with our own experience as free agents, as ‘manifestations of the one thought which is the law and meaning of the whole’, of ‘a supreme self-determination which ever lives and ever founds the order of things’. [18]

Recapitulating the ‘insuperable difficulties’ of pantheism, Bowne writes that the conception of all things and thoughts and activities as divine is ‘unintelligible in the first place, and self-destructive in the next’. To go beyond saying that God knows, understands, and appreciates our thoughts and feelings leads to both ‘psychological contradition’ and the ‘suicide’ of reason. It implies that ‘it is God who blunders in our blundering and is stupid in our stupidity, and it is God who contradicts himself in the multiltudinous inconsistencies of our thinking. Thus error, folly, and sin are all made divine, and reason and conscience as having authority vanish’. [19] In the sequel, we find a full restatement by Bowne of the main theme of the Schellingian and speculative theist criticism of Hegelian and similar pantheism:

[Block quotation:] What is God’s relation as thinking our thoughts to God as thinking the absolute and perfect thought? Does he become limited, confused, and blind in finite experience, and does he at the same time have perfect insight in his infinite life? Does he lose himself in the finite so as not to know what and who he is, or does he perhaps exhaust himself in the finite so that the finite is all there is? But if all the while he has perfect knowledge of himself as one and infinite, how does this illusion of the finite arise at all in that perfect unity and perfect light? There is no answer to these questions so long as the Infinite is supposed to play both sides of the game. We have a series of unaccountable illusions, and an infinite playing hide and seek with itself in the most grotesque metaphysical fuddlement. Such an infinite is nothing but the shadow of speculative delirium. These difficulties can never be escaped so long as we seek to identify the finite and the infinite. Their mutual otherness is necessary if we are to escape the destruction of all thought and life. [20]

This mutual otherness is also demanded by morality and religion. Pantheism is ‘inconsistent philosophical speculation’, not religion. The latter demands ‘the mutual otherness of the finite and infinite, in order that the relation of love and obedience may obtain’. The union sought by love and religion ‘is not the union of absorption or fusion, but rather the union of mutual understanding and sympathy, which would disappear if the otherness of the persons were removed. Any intelligible or desirable longing after God or identification with him would vanish if we should “confound the persons”.’ [21]

Bowne’s ethics is in my view much less developed as a specifically personalist one than that of the speculative theists or of Seth. As we have seen, Grubbe held that the theistic view of the source and the authority of the moral law had often been distorted and not understood with sufficient purity or philosophical precision. Bowne similarly voices reservations against simplistic renderings of it. [22] Rather than ‘formal moral judgements’, for him, Christianity has contributed ‘extra-ethical conceptions which condition their application’, and ‘moral and spiritual inspiration’. In outline, Bowne shares the European personalists’ understanding of the moral law. It is not, he says, ‘merely a psychological fact in us, but also an expression of a Holy Will which can be neither defied nor mocked’. Christianity sets the principles of the old law in a new setting ‘which makes them practically new’. Our moral nature is the same, but ‘the conditions of its best unfolding have been furnished’ in that ‘Love and loyalty to a person take the place of reverence for an abstract law. The law indeed is unchanged, but by being lifted into an expression of a Holy Will it becomes vastly more effective.’ The characteristic connection between ethics and religion is equally clear: Christianity ‘sets up a transcendent personal ideal which is at once the master-light of all our moral seeing, and our chief spiritual inspiration’. [23] It is striking, however, that Bowne does not in his ethics develop these concepts philosophically to anything close to the extent that the Europeans do. As we have seen, Knudson claims that Bowne’s is the most distinctive form of personalism. But it is hard to see that Bowne’s ethics is more distinctively personalist than that of the earlier or contemporary Europeans. This is confirmed by the fact that while dealing with the epistemological and metaphysical significance of the moral consciousness, Knudson’s book simply leaves out the specific treatment of the ethics of Bownean personalism.

Bowne rejects what he calls ‘objective eudemonism’, the standard form which has brought ‘eudemonism’ [24] in disrepute by seeking the ‘grounds’ of happiness without and neglecting ‘the siginificance of the personality within’ and ‘the demand for inner worthiness on the part of the moral subject’. But of course, he accepts the higher personalist sense of eudemonism: ‘All values, all goods, must finally be expressed in terms of the conscious well-being of the living self – in other words, in terms of happiness.’ But in personalist eudemonism, ‘happiness is largely determined by the reaction of the personality upon itself’. The ideal moral good is a positive concept, ‘conscious life in the full development of all its normal possibilities’, and its attainment involves the perfection not only of individual life but of ‘social relations’, and thus has community as its precondition. [25]

Formal, negative ethics is thus considered insufficient by Bowne as by all personalism. It is here that Bowne directly refers to Jacobi: ‘It was’, Bowne thinks, ‘the emptiness of all purely formal ethics which led to Jacobi’s famous protest in his letter to Fichte’. ‘[N]o sufficient law of life’, Bowne continues, ‘can be found in formal ethics alone, and…we must look not only to form but also to ends and outcome’. The negative view that the moral value of a deed is proportionate to the will’s overcoming of the passions or interests Bowne deems true only ‘from the side of merit’. The positive view is the true one ‘from the side of the ideal’. In this view, ‘the easier the deed the better; as when the will and desires move together in well-doing, and righteousness has become incarnate in the entire nature’. In the personalist version of this classical German idealistic neohumanism, which Bowne represents, the positive view is ultimately not merely an ideal of action; it is an ideal of being, of personality: ‘Moving inward from the deed to the doer, we find at once the personal source and the personal incarnation of the deeds. Here we come upon life itself, and we judge it not only by its intermittent manifestations but by its abiding principle. This is character, the final object of all moral approval or condemnation.’ [26]

This positive content and the ends of Bowne’s personalist eudemonism are, however, not just individual but both individual and social. It is crucial to be clear about the exact relation between these in Bowne’s philosophy. Not only is social ethics and its common good not exhaustive – ‘The moral ideal binds the individual…also in his self-regarding activities and thoughts’ – but ‘the centre of gravity of the good lies within the person himself’. There is, Bowne writes, no common good if any individual ‘is sacrificed in his essential interests, or is used up in his service’. The individual must share in the good he produces; he ‘may never be regarded as fuel for warming society’: ‘In our zeal against our native selfishness, we must not overlook the fact that the individual has rights against all others, singly or combined, and that in a moral universe provision must be made for maintaining them.’ When Bowne, as the only alternative to theories of force and values, affirms the moral person as ‘the unit of values in the moral system’, an unconditional end in itself from which all other ends ‘acquire their chief significance’ and to which they ‘owe all their sacredness’, with an absolute value in himself without which ‘no community of such persons can have any value’, [27] we must keep in mind that the moral person is conceived by Bowne in the personalist manner as concretely individual, in contradistinction to the general rational personality of Kant.

Bowne, like some of the early speculative theists in the age of neohumanist idealism, speaks of ‘the ideal of humanity’. The individual is ‘not simply the particular person, A or B, he is also a bearer of the ideal of humanity’. Bowne writes, on the one hand, that the duties to self which must in a sense ‘take the first rank in ethics’ consist in the individual’s ‘regarding in both its positive and its negative bearings’ this ideal in his life, in ‘developing and realizing’ it by ‘the due unfolding’ of his powers. But on the other hand, the ideal not only depends for its realization ‘pre-eminently upon himself’; it is abundantly clear that it can be realized only in himself qua individual, that his and others’ individuality is ontologically primary and not subordinate to the ideal as an impersonal universal. This becomes particularly evident in Bowne’s view of society. Not even the ideal of society is the ‘incarnation of the moral order of the world’, the ‘end of human development’, with the individiual existing only as ‘the material for filling out the social form which…has supreme value in itself’. Society is instrumental. Although as such, it has authority and may legitimately use coercion within its sphere, ‘the individual is the only concrete reality in the case, and…all social forms…must be judged by their relation to the realizing of personal life. The family, the state, the church have no value or sacredness in themselves, but only in their securing the highest good for living persons.’ [28] But more than this, Bowne elsewhere explicitly, and consistently with his general philosophy, states that ‘the race’, ‘the species’, and ‘humanity’ are mere logical fictions. Christianity took ethics beyond the limitations of the ‘narrow world view of the Greeks’ as well as of ‘the externalism of modern secular philanthropy’. The ethics of both of these was marred by generalism. Bowne’s criticism of philanthropy is particularly characteristic. Having

[Block quotation:] no outlook beyong things seen, and no power to cleanse more than the outside of the cup and platter, [it] must confine itself to sanitation, model tenements, the distribution of soup, and similar matters. These things are no doubt good, and, in their way, necessary; but they lead to so little for the individual that the sure outcome of this kind of thinking is to replace the individual by the “race” or the “species”, or “humanity”, or some other logical fiction, as the thing to be worked for. [29]

Reading this criticism, one thinks not primarily of the utilitarians, but, although the description does not fully fit them, of Upton’s criticism of the absolute idealists, who in this regard were not so far from them, Bosanquet engaging in social work in London’s East End. Philanthropy was of course rather an idealistic phenomenon than a utilitarian one. But the main point here is that it follows from Bowne’s criticism that the ideal of humanity must in itself include man’s individuality and not merely be an abstract universal exhortatively set against it. This is confirmed when Bowne states that ‘moralized humanity, or the moralized human person in a moralized society, is the highest good possible to us’ – the relation between the person and society being the one just described. In reality, when Bowne speaks of the ideal of humanity, he refers not to a something collectivly and uniformly realizable by the species, but to certain eminently human qualities which the individual should, and alone could, realize. This becomes more obvious when he exchanges ‘ideal of humanity’ for ‘human ideal’: ‘A complete law of duty for us must include both a human ideal and also a law of social interaction.’ [30]

This insight into the primacy of concrete individuality with regard to both reality and value, and the view of moral and axiological universality and objectivity as indissolubly manifest only in this distinctly, more-than-Hegelian concrete form that is the properly personal one, suffuses the whole of Bowne’s social and political philosophy. It should by now be plain that Bowne’s personalism represents a direct continuation of the European tradition; and there is no need to argue against Breckman that this tradition is not politically reactionary as taken over, restated, and developed by Bowne. Rather, it is necessary to point to the continuity with the conservative side of the earlier European tradition. Bowne’s social and political philosophy is strongly reminiscent of the moderate, historicist, and creatively traditionalist liberalism of the best among the European personalists in its criticism of a priori speculation and deduction, of abstract formulae and abstract hypostatization of society, of abstract individualism, of abstract universal philanthropy, of the excesses of democracy, of license, of the homo oeconomicus of classical political economy, and of utopianism.

Bowne’s personalism is clearly a modern phenomenon, and as such it does contain not only many distinctly modern philosophical elements, but also portions of a more general humanism which are absent from classical Christian orthodoxy and which set it apart from pre-modern intellectual currents with which in other respects it has much in common, even as these latter currents, like those contained in Augustinianism broadly defined, in their personalistic features contain seeds precisely of the modernity Bowne espouses. It must be admitted, Bowne writes, that ‘while the great inspirations of life come from the Christian world-view, the concrete forms of duty must be found mainly in the life that now is. This is the important truth in secularism, the truth which religiosity has so often missed.’ Although, with the exception of the term ‘secularism’, this could probably have been written by Luther or Wesley, it does, alongside the general if by no means unqualified historical progressivism which he shared with most personalists and other nineteenth-century idealists, indicate the modern, and not unproblematic, humanist element in Bowne’s thought. But it is interesting to see how he always keeps this humanism connected to his religion, how aware he is of the errors and dangers of secular humanism. Reaching the conclusion with personalist eudemonism that the ‘realization of normal human possibilities is…the only conception possible of human good’, he immediately goes on to point out that this ‘is true even if we adopt a mystical religious view, as, for instance, that God is the supreme good; for plainly in such a view there is the implicit assumption that thus we should reach the highest and truest spiritual life’. It is also interesting to see how very much aware Bowne is – again like other personalists – of the constitutive limitations of this life and this world. ‘Ideal character’, Bowne says, is possible under ‘untoward circumstances’, but ‘ideal life’ requires ‘an ideal environment’ which ‘[a] world like the present, where the creature is most emphatically “made subject to vanity”’, can never provide: ‘When science has done its best, and when the evil will has been finally exorcised, there will still remain, as fixed features of earthly life, physical and mental decay, bereavement and death; and none can view a life in which these are inevitable as having attained an ideal form.’ [31]

And as for Pringle-Pattison and Upton, these imperfections have a meaning. For Bowne, the world is ‘a training school for character’. [32] Only for abstract, academic speculation does the problem of the compatibility of pain and suffering with ‘infinite benevolence’ arise, the view that such benevolence ‘might as well make us happy at once and without effort on our part’, ‘as if the only good in life were passive pleasure, and the only evil passive pain’. But life’s values are revealed, and tested, only in life. Bowne’s theodicy is thus the same as that of the British personal idealists, sharing the same spirit of Victorian idealism at its best, free from sentimentality, and fittingly expressed in the same unpompous and modestly ornate style:

[Block quotation:] To all this life itself is the answer. The chief and lasting goods of life do not lie in the passive sensibility, but in activity and the development of the upper ranges of our nature. The mere presence of pain has seldom shaken the faith of any one except the sleek and well-fed speculator. The couch of suffering is more often the scene of loving trust than are the pillows of luxury and the chief seats at feasts. He that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow, but we would not forego the knowledge to escape the sorrow. Love, too, has its keen and insistent pains, but who would be loveless on that account? Logic and a mechanical psychology can do nothing with facts like these; only life can reveal them and remove their contradiction. [33]

[1] Knudson neatly summarizes its importance for personalism: ‘As over against absolute idealism personalism…is realistic in the sense that it maintains that existence is something other and deeper than thought. To set a thing in reality means more than simply to think it. It implies a deed, a creative act. How creation is possible we do not know, but the term at least brings out the distinctiveness of reality and the mystery that surrounds it. The soul is more than a thought-process; it is the source of thought rather than its product. This holds true of God as well as of man. Real existence is personal, not simply ideational; it is spiritual, not merely logical. In thus emphasizing the concrete, the extralogical, the volitional character of reality personalism retains a realistic element that the absolute idealist seeks to dissolve away.’ The Philosophy of Personalism, 225-6.

[2] Bowne, Theism, 164, 206, 218.

[3] Knudson, The Philosophy of Personalism, 65.

[4] Ibid., 66, 104, 107.

[5] Bowne, Theism, 288-90.

[6] Bowne, The Principles of Ethics, 107.

[7] Bowne, Theism, 287-90.

[8] Bowne, Personalism, 96, 278-9.

[9] For Howison, the social nature of personalism was so fundamental that it became an argument against creation: just as the finite persons could not be persons, not be themselves, without their relations to each other and to God, God, being a person, could not be himself without his relation to the finite persons, and thus he could in no sense have existed without them: they are co-eternal with God, the existence of one involves the existence of the other. Howison significantly emphasizes that reciprocal rights and duties are a prerequisite of personality. The true independence and freedom of the finite self would be impossible if the latter was created, for then it would be nothing but the expression of the will and purpose of his creator. Knudson replied that the Deity might itself be social in nature, i.e. have personal distinctions within itself as in the Trinity, and that creation may be eternal, that God may be thought of as eternally creating free spirits; The Philosophy of Personalism, 60. Their true freedom is for Knudson perfectly compatible with their createdness. Although their creation is of course a mystery which transcends us, ‘[o]nly on the basis of a mechanical conception of causality can it be claimed that every effect must be predetermined by its cause. Of a free Creator it certainly may be affirmed that he can create in his own image, even though the process is hidden from us’; ibid., 58-9.

[10] Bowne, Personalism, 280-1.

[11] Ibid., 96, 271, 273-7.

[12] Ibid., 276-8. Bowne takes over Lotze’s view of the interaction of the Many through the One; Knudson, The Philosophy of Personalism, 197-200.

[13] Bowne, Personalism, 20-1, 25, 53.

[14] Bowne, Theism, 231-3

[15] Bowne, Personalism, pp. vi-vii.

[16] Ibid., 104, 106, 160-2, 187-8, 197-8.

[17] Ibid., 215-16.

[18] Ibid., 177-9.

[19] Ibid., 282-3.

[20] Ibid., 283-4.

[21] Ibid., 284-5.

[22] Bowne, Theism, 253; Bowne, The Principles of Ethics, 188.

[23] Bowne, The Principles of Ethics, 201-2.

[24] I use Bowne’s spelling in this section.

[25] Bowne, The Principles of Ethics, 55, 57, 69.

[26] Ibid., 35, 122-3.

[27] Ibid., 72, 113, 199, 208-9.

[28] Ibid., 209, 252.

[29] Ibid., 203.

[30] Ibid., 69-70, 111.

[31] Ibid., 69-70, 73-4, 204.

[32] Ibid., 74.

[33] Bowne, Theism, 280-1.

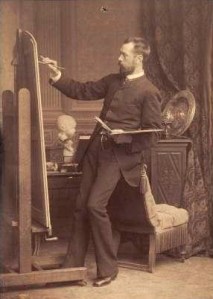

Kronberg, Johan Julius Ferdinand, målare, f. 11 dec 1850 i Karlskrona [d. 1921], kom 1863 till Stockholm, började 1864 teckna i konstakademiens principskola och blef 1865 uppflyttad i antikskolan. Hans lärare blefvo J. C. Boklund, A. Malmström och en kortare tid J. Höckert, hvars konst på honom utöfvade mycken inverkan. 1868 målade han prisämnet ‘Johannes i öknen’ och vann 1870 k. medaljen för ‘Gustaf Vasa mottager bibelöfversättningen’. Under väntan på resestipendium målade han ‘Ebba Brahe vid fönsterrutan’, åtskilliga smärren genre och landskapsbilder i olja och akvarell (‘Kyrkstöten’, köpt af Karl XV, ‘I Nacka kapell’ m. fl.) och 1873 den lifligt komponerade akvarellen ‘Marknadsscen på 1500-talet’ med Erik XIV och Karin Månsdotter som hufvudpersoner. S. å. erhöll han statens resestipendium, besökte under idkande af studier Köpenhamn, Paris och Düsseldorf (bland arbeten från denna resa ‘Page, insomnad bland blommor’ och ‘Kalkonvakterska’) samt slutligen München, där han slog upp sin ateljé 1874. Där utförde K. 1875 sitt första betydande verk, ‘Jaktnymf och fauner’ (Nationalmuseum). Den ungdomligt blodfulla och lifskraftiga taflan vittnade om en koloristisk djärfhet i anslaget, som var något helt nytt i den tidens försiktiga svenska måleri, och om en skicklighet, en bravur, som öfverträffade allt, hvad svenska konstnärer då kunde framvisa. Efter fullbordandet af ‘Jaktnymfen’ hösten 1875 reste K. till Venezia, där han under ett par månaders tid egnade sig åt studiet af de gamle mästarna och lade grunden till den samling af utmärkta kopior och färgskisser efter de gamle, hvilken han under årens lopp alltmera ökat. Återkommen till München, grep han sig an med en ny stor uppgift, och under loppet af år 1876 fullbordades den stora behagfulla allegorien ‘Våren’ – vårens gudinna bäres genom luften på en storks rygg och omges af amoriner och putti. I München målade K. bl. a. ett porträtt af H. Ibsen (1877). Åren 1877-89 var K. bosatt i Rom, med undantag af en resa 1878-79 till Egypten och Tunisien. I Rom målades ‘Amorin’ (1878, Nationalmuseum), ‘Backant’ (1881, raffinerad i färgval och färgbehandling), samma motiv varieradt i akvarell (1882, Fürstenbergs testamente, Göteborgs museum), ‘Sommaren’ och ‘Hösten’ (s. å., sidostycken till den redan nämnda ‘Våren’, som nu ommålades, stämd i en ljusare, mera blond färgton…hvarjämte vårgudinnan fick en annan, yngre typ), ‘Kleopatras död’ (1883) m. fl. ‘Drömmen’ (s. å., en amorin hviskar i örat på en slumrande flicka i 1700-talsdräkt, scenen förlagd till Drottningholms park) och ‘På födelsedagen’ (en skrattande ung flicka med en bukett i en dörr, 1884) målades under konstnärens besök i Stockholm dessa båda år. ‘David och Saul’ (Rom 1885, Nationalmuseum…) betecknar ett omslag i K:s uttryckssätt – hans tidigare ungdomliga lust för koloristisk must och yppig rikedom har nu öfvergått till en lugn, stillsam hållning och ett enkelt, mera monumentalt behandlingssätt. Närmast följa nu de båda motstyckena ‘Romeo och Julia på balkongen’ och -‘i grafhvalfvet’ (1886), den stora duken ‘Drottningen af Saba’ (1888) samt ‘Hypatia’ (1889). Samma år flyttade K. hem till Stockholm. Han hade blifvit led. af konstakademien 1881 och vice professor 1885, blef ord. professor 1895, men begärde afsked från denna befattning 1898. Han utförde på beställning af Oskar II 1890-94 tre stora plafondmålningar för västra trappuppgången i Stockholms slott:

Kronberg, Johan Julius Ferdinand, målare, f. 11 dec 1850 i Karlskrona [d. 1921], kom 1863 till Stockholm, började 1864 teckna i konstakademiens principskola och blef 1865 uppflyttad i antikskolan. Hans lärare blefvo J. C. Boklund, A. Malmström och en kortare tid J. Höckert, hvars konst på honom utöfvade mycken inverkan. 1868 målade han prisämnet ‘Johannes i öknen’ och vann 1870 k. medaljen för ‘Gustaf Vasa mottager bibelöfversättningen’. Under väntan på resestipendium målade han ‘Ebba Brahe vid fönsterrutan’, åtskilliga smärren genre och landskapsbilder i olja och akvarell (‘Kyrkstöten’, köpt af Karl XV, ‘I Nacka kapell’ m. fl.) och 1873 den lifligt komponerade akvarellen ‘Marknadsscen på 1500-talet’ med Erik XIV och Karin Månsdotter som hufvudpersoner. S. å. erhöll han statens resestipendium, besökte under idkande af studier Köpenhamn, Paris och Düsseldorf (bland arbeten från denna resa ‘Page, insomnad bland blommor’ och ‘Kalkonvakterska’) samt slutligen München, där han slog upp sin ateljé 1874. Där utförde K. 1875 sitt första betydande verk, ‘Jaktnymf och fauner’ (Nationalmuseum). Den ungdomligt blodfulla och lifskraftiga taflan vittnade om en koloristisk djärfhet i anslaget, som var något helt nytt i den tidens försiktiga svenska måleri, och om en skicklighet, en bravur, som öfverträffade allt, hvad svenska konstnärer då kunde framvisa. Efter fullbordandet af ‘Jaktnymfen’ hösten 1875 reste K. till Venezia, där han under ett par månaders tid egnade sig åt studiet af de gamle mästarna och lade grunden till den samling af utmärkta kopior och färgskisser efter de gamle, hvilken han under årens lopp alltmera ökat. Återkommen till München, grep han sig an med en ny stor uppgift, och under loppet af år 1876 fullbordades den stora behagfulla allegorien ‘Våren’ – vårens gudinna bäres genom luften på en storks rygg och omges af amoriner och putti. I München målade K. bl. a. ett porträtt af H. Ibsen (1877). Åren 1877-89 var K. bosatt i Rom, med undantag af en resa 1878-79 till Egypten och Tunisien. I Rom målades ‘Amorin’ (1878, Nationalmuseum), ‘Backant’ (1881, raffinerad i färgval och färgbehandling), samma motiv varieradt i akvarell (1882, Fürstenbergs testamente, Göteborgs museum), ‘Sommaren’ och ‘Hösten’ (s. å., sidostycken till den redan nämnda ‘Våren’, som nu ommålades, stämd i en ljusare, mera blond färgton…hvarjämte vårgudinnan fick en annan, yngre typ), ‘Kleopatras död’ (1883) m. fl. ‘Drömmen’ (s. å., en amorin hviskar i örat på en slumrande flicka i 1700-talsdräkt, scenen förlagd till Drottningholms park) och ‘På födelsedagen’ (en skrattande ung flicka med en bukett i en dörr, 1884) målades under konstnärens besök i Stockholm dessa båda år. ‘David och Saul’ (Rom 1885, Nationalmuseum…) betecknar ett omslag i K:s uttryckssätt – hans tidigare ungdomliga lust för koloristisk must och yppig rikedom har nu öfvergått till en lugn, stillsam hållning och ett enkelt, mera monumentalt behandlingssätt. Närmast följa nu de båda motstyckena ‘Romeo och Julia på balkongen’ och -‘i grafhvalfvet’ (1886), den stora duken ‘Drottningen af Saba’ (1888) samt ‘Hypatia’ (1889). Samma år flyttade K. hem till Stockholm. Han hade blifvit led. af konstakademien 1881 och vice professor 1885, blef ord. professor 1895, men begärde afsked från denna befattning 1898. Han utförde på beställning af Oskar II 1890-94 tre stora plafondmålningar för västra trappuppgången i Stockholms slott: