Ezra Levant and Mark Steyn

on hate crimes legislation, free speech, the abuse of human rights ideology, the U.S. economy, the post-American order or non-order, pseudo-education, demographic and other decline in the West, Breivik and terrorism, freedom and rights in general, nationalist opposition, the problem with the media, the problem with world government, the need for borders, and more.

See also Ezra Levant and Mark Steyn on the Canadian Human Rights Act and Human Rights Commission (1-7)

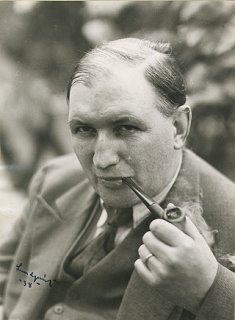

Alf Ahlberg

Alf Ahlberg (1892-1979) är mest känd för sin gärning som historiskt djupt förankrad, frihetligt demokratisk folkbildare vid Brunnsviks folkhögskola. Och för det framgångsrika, i stor utsträckning essäistiska författarskap i vilket han förmedlade sin åskådning och sina värderingar till en bred läsande allmänhet, sitt vältaliga försvar i många olika sammanhang för det klassiska bildningsarvet och humanismen i viss relativt noga bestämd mening, sitt distinkta urskiljande av denna humanisms historiska linje i västerlandet, sina introduktioner till filosofins historia och enskilda filosofer, sin kritik av den moderna totalitarismen, sin inte minst psykologiska analys av den moderna propagandan och dess effekter, och i någon mån kanske också sina många översättningar.

Men Ahlbergs något “smalare” filosofiska verk från hans tidiga period i Lund – där han var Hans Larssons favoritstudent – förtjänar i lika hög grad uppmärksamhet. Ahlberg ger i dem en tydlig och karaktäristisk, av traditionen från Geijer och Boström direkt och explicit influerad personlighetsfilosofisk turnyr av Windelbands och Rickerts samtida värdefilosofiska nykantianism (den s.k. Badenskolans), som i flera avseenden är av bestående värde och intresse. Det är de ståndpunkter han här artikulerade som ligger till grund för hans senare, bättre kända författarskap och allmänna kulturella gärning, och för den som är förtrogen med dessa ståndpunkter är de där ofta lätt igenkännbara. Inte minst genom Ahlberg kom den svenska personlighetsfilosofin på detta sätt att i viss utsträckning forma en central bildningslinje också i nittonhundratalets svenska kultur.

Liksom på sitt sätt John Landquist och tidigare Vitalis Norström förnyade och varierade Ahlberg den personlighetsfilosofiska traditionen. Visserligen förlorades några centrala dimensioner av denna, men den distinkta åskådnings- och värdemässiga profilen måste ändå hos alla dessa, och inte minst Ahlberg, i stor utsträckning sägas ha bevarats och vidareförts inom den delvis nya epistemologiska och metafysiska ramen.

Filosofiskt är det möjligt att gå djupare, och för att göra det måste man snarare gå tillbaka till eller i alla fall gå via den mer konsekventa och fullgångna typ av filosofisk idealism som senboströmianerna och andra vid samma tid fortfarande åtminstone försökte försvara. Idag kan vi, insisterar jag, lättare än dessa se de vida perspektiv denna typ av filosofi öppnar – inte bara genom tydligare historiska linjer bakåt i den västerländska filosofihistorien, utan också genom ny tillgång till komparativa studier och fördjupad introduktion inte minst av den vedantistiska traditionen.

Även omfattande ny forskning om artonhundratalsidealismen – och inte bara den tidiga tyska – har bidragit till en långt bättre kännedom om vad som länge lättvindigt avfärdades med hjälp av enkla karikatyrer, och filosofer har åter försvarat, nyformulerat och vidareutvecklat idealismens ståndpunkter. Allt detta underlättar förståelsen, historiskt och filosofiskt, av vad det i själva verket handlade om.

Denna idealism var, i dess svenska variant, den tradition i vilken Ahlberg formades. Den nödvändighet av personlighetsfilosofins nykantianska och övriga modifikationer som han med Landquist och Norström var övertygad om framstår idag i flera centrala avseenden som mindre självklar. Ändå har vi också hos Ahlberg på många punkter att göra med insikter som några av de bästa filosoferna idag, efter de olika pragmatiska, analytiska, fenomenologiska, existentialistiska, kritisk-teoretiska, strukturalistiska och i vid mening postmodernistiska och postmarxistiska riktningarnas långa dominans och därmed den beklagliga historiska diskontinuiteten, ibland förefaller s.a.s. kämpa onödigt hårt för att återfinna, återupptäcka, nyformulera. Ahlberg inte bara kvarhåller insikter från den äldre traditionen, utan omformar också de distinkta bidragen från sin egen tids främst tyska tänkande på ett sätt som åtminstone delvis böjer dem till harmoni med dessa insikter, ja möjliggör nya distinkta, i sig värdefulla uttryck för dem.

Jag har tidigare här i bloggen postat kortare texter om svenska personlighetsidealister hämtade från första upplagan av det av Ahlberg redigerade Filosofiskt lexikon (1925).

Plaza Hotel, Buenos Aires

1910

Tino Sanandaji

The Kurdish-Swedish economist, Tino Sanandaji, who is currently a doctoral student at the University of Chicago and who appeared at the recent seminar about multiculturalism organized by Axess in Visby which I mentioned in my post ’Almedalen’, reiterates in a blog post in English the arguments I supported in my post but also reveals what can now clearly be seen to be the weakness of his position.

Sanandaji is right that ”multiculturalism has failed”; that it has been replaced at least by some of those who no longer believe in it by ”anti-anti-multiculturalism”; that when we speak about the problems of multiculturalism we define culture as ”the informal rules of the game of society, informal institutions, etiquette, traditions, norms and values as opposed to superficial cultural expressions such as what food you eat and what music you listen to”; that ”if you have different rules for different people”, as the multiculturalist ethnic separation and ”institutionalized segregation” prescribes, ”society doesn’t function smoothly”; that multiculturalism is poorly thought out and that in all likelihood its proponents do not themselves realize its full implications; that multiculturalism hurts immigrants, who are often unable to integrate, who fail to ”learn all the many subtle rules which guide life in Sweden” and are unable to ”add a Swedish identity to the one they already have”; that those immigrants are often ”embittered, and react by adapting the ghetto-culture of the United States, as a way to mark distance to mainstream society”, that ”[t]he personal consequence for immigrants from being unable to integrate is mass unemployment, low income, crime ridden neighborhoods, and social isolation”.

Sanandaji is also right that multiculturalism has been promoted not just by the socialist left but by ”left-libertarians” (specified by Sanandaji in a comment as “cultural Marxists”), who ”promise immigrants that they can migrate to Sweden and maintain all their traditions and norms and behavior from Afghanistan and Albania, without any cost to themselves”, that ”the left-libertarians have bullied the right into proposing open borders, in order to prove they are not racist”; that ”[t]his policy has never been attempted by any country in modern history”; that ”[o]pen borders is a social experiment on the grandest scale, yet its proponents have hardly thought it through, other than through clichés and slogans”, and that ”[n]ot surprisingly, open borders does not have any electoral support in Sweden”.

Finally, he is right that ”the solution to the obvious failure of multiculturalism is for Sweden to regain the cultural self-confidence it requires to integrate immigrants”, that ”[a]s an immigrant it is impossible to integrate into nothingness, you need a clearly defined pole of Swedish culture, which must be open to immigrants, in order for more to gravitate towards Swedish culture and be accepted into society”; that integration does not mean immigrants have to give up their native identities, that multiple identities are possible; that left-libertarians are dogmatically obsessed with open borders.

These are all excellent and centrally important points which I fully endorse. But contrary to Sanandaji’s Visby presentation, the blog post clearly displays weaknesses that unfortunately cannot be ignored.

First of all, Sanandaji’s understanding of culture and rules seems superficial in a way that unduly confines the analysis of multiculturalism within limits set by the economist’s perspective. His statement that ”[t]he rules imbedded in culture are to a large extent there in order to reduce transaction costs in a society” of course implies that the culture that the rules are embedded in is something more than the rules themselves, yet even if “costs” is understood in a broad sense, the formulation that the purpose of the rules produced by the culture is to a large extent to reduce transaction costs is a reductionism that is not sufficient for the understanding and analysis of all aspects of multiculturalism or the multicultural society.

This may be too negative an interpretation, yet it does seem to me the tendency seen here probably accounts to some extent for Sanandaji’s problematic view that ”the people hurt most by multiculturalism are immigrants”. This can be so only in a very limited perspective. It is of course true that many immigrants who are unable to integrate are hurt by multiculturalism. But the statement is shallow in view of the demographic development in the Western countries that receive the immigrants. If present developments continue, the immigrants with their respective cultures will within a not too distant future become majorities in Western Europe as well as in the United States. Not just allowing but encouraging an ever growing flow of new immigrants to maintain their native cultures, and discouraging cultural integration, multiculturalism hurts non-immigrants, the ethnic white populations of the West as well as their culture (and those of other origins who have truly become parts of that culture), much more than the immigrants.

Sanandaji is also utterly unrealistic in his view of both the possibility and the actuality of integration. ”[H]undreds of thousands of immigrants in Sweden have integrated and adopted multiple identities, which proves my point. We just need the other half [the hundreds of thousands of immigrants who have not done so] to do the same.” But it is true that many immigrants have successfully integrated, and Sanandaji rightly stresses this. ”Learning Swedish doesn’t mean you have to forget your native language. Learning the informal rules which guide work and social life doesn’t mean you have to forget the rules from your home country. You can be proud of your Kurdish heritage, but simultaneously proud of your Swedish upbringing and citizenship.” Sanandaji is also right that more will do so with the solution he proposes, the stronger assertion of Swedish cultural identity.

It seems to me this solution would perhaps be sufficient if at the same time the current mass immigration were stopped and the demographic trend with regard to ethnic Swedes reversed. Vast and difficult questions are involved here which I cannot embark upon a discussion of in this post. But with the current rate of immigration on the one hand and demographic decline on the other, the suggested solution can hardly be enough. The unmanagable numbers of new immigrants often already do not have the motivation to adapt to and integrate into a vanishing culture.

It is astonishing that Sanandaji, who now lives in the United States, maintains illusions about that country that could perhaps to some extent still be entertained in the Reagan era but which are today obviously and increasingly absurd. He does write that e pluribus unum is ”the historical American ideal”, but at the seminar he made it perfectly clear that he thinks the ideal is still being realized today, that all American citizens share an Anglo-American culture, the one established by the British colonists and the Founding Fathers.

If that is so, where does ”the ghetto-culture of the United States” which Sanandaji complains about both in the blog post and in the seminar come from? It is of course produced by mechanisms in the United States similar to the ones he describes as being at work in Sweden (and, of course, by the same entertainment moguls and for the same purposes). Latino immigrants are currently taking over or “reconquering” large parts of the South-West including California, insisting on keeping to their own culture (which is still in important respects Western!), and displaying open and sometimes violent hostility against the allegedly unifying Anglo-American, i.e. basically and originally British and European, culture and its bearers. Similar long-standing and well-known tendencies can be found among the black ”minority” which, together with the Latinos and others, will soon have outnumbered the white Americans of various European origins if the current trends are not reversed. The fact of American disintegration is well-established and has long been thoroughly documented by scholars. America is quite as much in need of the cultural assertion Sanandaji recommends as is Sweden – and not just in order to reduce transaction costs, but to preserve and renew the deeper values of its historical civilization.

Then there is the issue of ”classical liberalism”. This, as used by Sanandaji, is a vague concept. While distinguishing ”classical liberalism” from ”left-libertarianism” (represented in Sweden today by, for instance, Johan Norberg and Carl Rudbeck) and rightly rejecting the latter, he includes in the concept of classical liberalism not just classical libertarianism, not just the late eighteenth-century liberalism and its philosophical predecessors, but also John Stuart Mill.

Sanandaji is right to point out that ”classical” liberalism does not support the ”insane idea” of open borders. This point is well taken and easily proven by reference to Smith and Burke. But Sanandaji underestimates the radical, combined rationalistic and romantic inspiration and impetus of much else of what he evidently regards as ”classical” liberal thought, which in the course of the nineteenth century, and already in liberals like Bentham, Ricardo, James and John Stuart Mill, Bastiat, Say, and Cobden, manifested itself in conceptions which cannot be described as anything but utopian. In the light of such cases, the transition from ”classical” liberalism to ”left-libertarianism” appears perfectly natural and logical.

Sanandaji’s preferences in terms of party politics at least become comprehensible in view of these weaknesses in his analysis. He hopes to be able to persuade what he misleadingly calls “the right” in Sweden to adopt what he thinks is “classical” liberalism, and to apply it to end the ideology and the policies of multiculturalism. He finds the “reform agenda” of Reinfeldt and Borg “urgently needed”. What precisely does he have in mind here? Reduced taxes, no doubt. More privatization. More simplistic capitalism. But then he will have to be more specific with regard to much else that we know is on the same agenda. How about more integration into the EU that is clearly not prevented by its basic capitalist purposes from becoming increasingly Sovietized in terms of ideological thought control? More adaptation to the dictates of the old socialists in the IMF? More centralized globalism in general? Here Sanandaji, taking the positions he does on borders, cultures, and integration, surely must draw the line.

Still more directly pertinent to his main agrumet: how about the further increase in Europe’s extreme mass immigration – the current mass immigration as such? In an earlier article in Svensk Tidskrift, Sanandaji does question the current level of third world immigration, with regard to its effect on the economy and immigrant support for leftist welfarism. It would have been helpful to add reduced immigration per se to what is now his explicit plea only for integration by means of Swedish cultural self-assertion. Without it, the latter will, as I have shown, hardly be enough.

How will the Swedish “right”, i.e. the Reinfeldt government alliance, persuade the increasingly dominant – culturally as well as numerically – immigrants to vote for it and its agenda? This is one of the problems Sanandaji himself addressed in Svensk Tidskrift: the truth is that they will rather consolidate indefinitely the high-tax welfare state that Sanandaji opposes. And how will Reinfeldt’s government, itself known from the outset for its drastic lurch to the left (“cultural Marxist”, left-libertarian etc.), ever be able to implement the mentioned agenda if its new coalition partner will be the often quite extremely leftist Green Party?

The only theoretically conceivable way for the right to succeed in what Sanandaji wants it to accomplish with regard to integration is an agreement with the Sweden Democrats. But precisely this is what Sanandaji now says it is his very purpose to forestall. Since the Sweden Democrats declared that they were ready to accept Reinfeldt’s tax reductions if Reinfeldt accepted their immigration policy or parts of it, this stance makes it unclear to what extent Sanandaji opposes the current immigration, in terms of numbers.

”Some people have come up to me, said that they agreed with me, but expressed concern that I was helping the anti-immigration party The Sweden Democrats”, Sanandaji writes. ”The truth is the opposite.” Indeed, Sanandaji attempts to ”offer an alternative to the Sweden Democrats, to keep voters who observe that Sweden’s current policies are not working but who do not dislike immigrants from being forced to abandon the right”.

This is of course the same move we have already seen Merkel, Sarkozy, and Cameron make, and they were all mentioned by Sanandaji in Visby. He is certainly right that the Swedish “right” too must follow the Sweden Democrats or perish. He is also right that they are currently choosing to perish, and, to judge not just from their current immigration deal with the Greens but also their signalled further regular government alliance with them, they are doing so very consciously. For even if they don’t understand or care about the destruction of Swedish culture and the disapperance of the Swedish people, surely they must understand that the continued mass immigration will forever make tax reductions, the reduced welfare state, and what with the ever Marxist-influenced Swedish terminology they call the ”bourgeois” values forever impossible. (The terminology is of course not exclusively Marxist, but it is, as I have often pointed out, because of the Marxist usage promoted by the exceptionally long and strong dominance of the left in politics and academia that it has become so prevalent in Sweden also as the centre-right’s own; cf. France, Germany, Britain.)

Sanandaji is undeniably on target when he says that ”[b]y pushing open borders as the only alternative on the right and shouting down any problematization of immigrant segregation as racist, some young voters are forced into the Sweden Democrat column”, that [b]y radicalizing the right, branding any dissent as racist and beating the drums of open borders libertarians are the ones who are helping the Sweden Democrats.” He is to some extent right that ”if the right had taken the concerns of voters about crime, welfare dependency and segregation into consideration, the Sweden Democrats would not even be in parliament in the first place”, although he should have added the implied issue of Swedish cultural assertion. His observation that the left-libertarians’ shameful treatment of Svenska Dagbladet’s Per Gudmundson when he stated some unpleasant truths and statistics, their joining with the socialists in demonizing him, helped the Sweden Democrats to take more voters ”from us” – i.e., from him and his fellow Reinfeldters – is wholly true. ”Why do we still allow a small number of shrill ideologies to erode electoral support for the Right, by driving all those who don’t share their extremist and unpopular ‘abolish-all-borders’ positions into the open arms of the Sweden Democrats?”, Sanandaji asks. And it is a very good question.

Only there is no problem here. There simply is no problem in the disappointed voters turning to the Sweden Democrats because of all of the calamities of the “right”. They quite rationally and legitimately do so because the Sweden Democrats are the only party which presents a tenable alternative. There is nowhere else they can go when the right commits suicide before their very eyes. And there is nowhere else they need go or should go. Indeed it is the Sweden Democrats alone who offer precisely the alternative Sanandaji himself presents, plus the essential and decisive missing pieces and minus his inconsistent apparent support for the whole of the rest of the Reinfeldtian agenda. Only in the open arms of the Sweden Democrats can they really achieve the policy changes Sanandaji advocates.

Sanandaji complains that the Sweden Democrats are ”joining with the socialist left in sabotaging” Reinfeldt’s agenda. But again, he knows that this agenda is a globalist one of the kind he himself in at least some central respects must oppose. His sweeping support for it is simply not congruent with his own main argument. The Sweden Democrats are ”sabotaging”, i.e. opposing the agenda, trying to stop it, because they don’t believe in it, because they are against it. Tax reductions are acceptable to a certain extent if their own immigration reforms – which would of course mean enormous reductions of public spending and thus in themselves make possible even further lowered taxes – are accepted, but definitely not otherwise. Much more than that is on Reinfeldt’s agenda, however, and not just mass immigration. Things which Sanandaji too must logically reject. It seems to me he is naive to think that “[t]here is no reason why we can’t have more classical liberalism” in his sense (i.e. ”as opposed to the current combination of cultural marxism or left-libertarianism”) “in these questions among the already existing right-of-center parties”. There are many such reasons.

Sanandaji’s true points summarized above are severely undermined when he himself repeats the ”clichés and slogans” he rightly blames the leftists and left-libertarians for using. The Sweden Democrats, he implies, ”dislike immigrants”. They are ”xenophobic”. In a comment to his post, where in response to a critic he lists three ”fundamental differences” between himself and the Sweden Democrats (he in fact says there are several fundamental differences but that he mentions only three) , Sanandaji gives a typically nonsensical description of the latter.

First of all, they are, he charges, an outgrowth of “the skinhead and neo-Nazi movement”. “I am not”, he writes, “going to forgive the Swedish communist party for supporting Stalin 60 years ago, why should I forgive the Sweden Democrats for being a neo-nazi parti until 10 years ago?”

I have discussed this criticism before in connection with my analysis of Tradition & Fason’s statements about the Sweden Democrats, but because of the attention given to Sanandaji’s recent contributions to the political discussion in Sweden I now have to return to it and develop my response at greater length.

Another commentator immediately steps in and points out that Sanandaji doesn’t know as much about the Sweden Democrats as he does about other things. There is, she shows, a scholarly consensus that the Sweden Democrats are not and have never been a national socialist party, and that this consensus is shared even by far-left and anti-antisemitism organizations.

There is also, however, what seems to be a common position according to which the Sweden Democrats cannot have national socialist origins and cannot have had any national socialists among their members since there simply are no national socialists in Sweden. I reject this position as facile and deceptive. When I first discovered the Sweden Democrats at the time of the general elections in Sweden in 2006, I began what I think I may perhaps be allowed to describe as a comparatively thorough study of the various currents of Swedish nationalism in the twentieth century, my knowledge of nationalism having up to that point been mainly limited to nineteenth-century and to some extent early twentieth-century forms of it in Sweden, and to French nationalism, Italian fascism, and German national socialism. It was necessary in order to understand the Sweden Democrats, not least but certainly not exclusively in view of the standard criticisms, and in order properly to situate them in terms of ideology and twentieth-century Swedish political history, to get a firm grasp of all of the various nationalisms in Sweden today and their respective genealogies.

It immediately became obvious that there are real national socialists in Sweden. There was Nationalsocialistisk Front, a party which was later absurdly renamed Folkfronten (the Popular Front, the name of the anti-fascist Comintern alliances of the 1930:s), and which then assumed its current name, Svenskarnas Parti (the Swedes’ Party). They now have a web journal called Realisten. There was also a non-party organization called Svenska Motståndsrörelsen, which somewhat distinguished itself by selling rare Swedish national socialist publications from the 1930:s and 1940:s that could not be found elsewhere. Then there was something called Nordiska Förbundet, which published a glossy journal and sold new national socialist and fascist books. I think I can claim to have studied all of these groups relatively closely through their publications, and there can be no doubt whatsoever that they explicitly call themselves national socialists and that they connect historically to the German national socialists and the post-war continuation and ideological variation of German national socialism in other countries. There is also, as I have more recently discovered, a website called Nationell.nu, run by a young law student, Richard Langéen, which seems to be at least sympathetic towards national socialism in some respects.

Against this background, it seems to me it is not a mystery at all that there were indeed some national socialists who were initially drawn to an at least partly nationalist party like the Sweden Democrats rather than to the anti-nationalist parties, especially at a time when that party was the only one with elements of nationalism or at least the only such party that showed any promise of becoming a successful one.

National socialist groups thus certainly exist in Sweden. But they do seem to be very small indeed. Moreover, while twentieth-century nationalism is a complex phenomenon with many widely divergent versions, and the more specific fascist movement too is a complex and difficult one, it must be kept in mind that national socialism, while it too shares the complexities, is also a very specific and, as it were, ”narrow” ideology in a certain sense. It is a measure of the general level, the poverty, and the crudeness of the conceptual instruments of the current political discussion as carried on in the media that even the most basic distinctions are not made within the vast spectrum of political groups and ideologies for which the concept of the nation is central.

As the Sweden Democrats have often insisted, the national element in their ideology is one that was widely shared by the other parties (except the communists) until the mid-twentieth century. Its roots are in the older, broader, and more general current of nationalism which goes back to the nineteenth century. And this implies considerable philosophical differences. As the cited commentator appositely points out, Sanandaji overlooks the attacks the Sweden Democrats were long constantly exposed to from radical Swedish nationalists of various kinds and are probably still exposed to. And the nature of those attacks. Deep and complex historical discussions, going back not just to the German national socialists and WWII, but much further, to WWI and beyond (as I have always pointed out, twentieth-century history as a whole looks different from my perspective than from that of the liberalism and socialism dominant since the post-war era) are called for, yet we see nothing of them.

On the other hand, these deficiencies are of course not surprising. They are the deliberately produced result of a well-known, thoroughly analysed, long-standing propaganda effort on the part of the left, the liberals, and the pseudo-conservatives. It is sad that a person so clear-sighted in other respects as Sanandaji seems to succumb to what is in reality a threat to the preservation, continuation and renewal of the best traditions of freedom and civilized order. We risk losing them in the false dichotomization of political correctness.

As for the ”skinhead” movement, I know almost nothing about it, so it is difficult for me to say something meaningful here. This I admit I have not studied. I have heard and read a little about skinheads, and, long ago, I have seen what I think must have been skinheads. But I don’t associate any particular articulation of political beliefs with this movement, no elaborate ideological positions of a kind that would make it plausible that a political party like the Sweden Democrats is an outgrowth of it. What is the skinhead ideology? Is it the same as national socialism or some version of it? Are there any distinctly ”skinheady” elements in the Sweden Democrat’s first programme? In one of my posts mentioned above I included a video from a meeting of the Sweden Democrats in Medborgarhuset in Stockholm in 1991, only three years after the party’s founding in 1988. Is there anything skinheady about that meeting?

Sanandaji’s second ”fundamental difference” is that the Sweden Democrats are, according to him, “obsessed with reducing the flow of immigrants. But they offer no constructive solution to the 1 million immigrants we already have. This is what I attempt to do (strong enough cultural self-confidence from Swedes for their own culture to integrate immigrants).” Here Sanandaji seems to downplay his earlier argument regarding the problems with much of the immigration as such, while accepting the propaganda that the Sweden Democrats are onesidedly “obsessed” with this issue only.

And his claim for his suggested alternative is strictly incomprehensible. Do the Sweden Democrats not offer the constructive solution of enough cultural self-confidence from Swedes for their own culture to be able to integrate the immigrants we already have? Apart from the reduction of the flow of new immigrants, it is hard to think of a political position that is more central to the Sweden Democrats and for which they are better known than precisely this.

Sanandaji’s third fundamental difference is that the Sweden Democrats ”join forces with the left and block cutting taxes for low-income workers”, according to Sanandaji the most efficient method for increasing the employment and thus the integration of immigrants. Granted that Sanandaji speaks here only about immigrants ”we already have”, and adding that we should be talking only about immigrants who are now Swedish citizens, there is still the problem that the right’s proposed tax cuts are mostly for high-income non-workers and not for low-income workers, even as they are to some extent also for the latter. Sanandaji also overlooks the vast issues of the other aspects of the globalization he seems to object to only with regard to the issue of cultural integration: deindustrialization, deagriculturalization, supranational corporatization and centralization, excessive offshoring, the increasingly precarious position of the middle class (which many scholars agree is central to the stability of prosperous and democratic societies) in the West in general – all issues decisive for any serious long-term discussion of employment.

Sanandaji’s presentation in Visby was favourably received by many Sweden Democrats. Some protest that too much attention is paid to people like him who often come so close to the positions of the Sweden Democrats as to be virtually identifiable with them, but then also at more or less regular intervals disown and repudiate that party in starkly disproportionate terms. It is true that more attention should not be paid to such persons than they deserve. And I have shown in what respects Sanandaji’s position is flawed.

But among those who try to offer an alternative to the Sweden Democrats in order to keep voters from abandoning Reinfeldt’s foreseeably sinking ship, Tino Sanandaji seems to be the one who comes closest by far to the rescuing Sweden Democrats on the issues of immigration in general, the integration of immigrants, the problems of failed integration, Swedish culture, nationality, the nation state, open-borders utopianism, left-libertarianism, and “cultural Marxism”. Such a person should not be given less attention than he deserves.

Edvard Bergh: Sommarlandskap

Edvard Bergh

Bergh, Johan Edvard, landskapsmålare, föddes i Stockholm 29 mars 1828, blef student i Uppsala 1844 och egnade sig där först åt naturvetenskapliga, sedan åt juridiska studier, tog hofrättsexamen 1849 och tjänstgjorde några år dels i Svea hofrätt, dels i Stockholms rådstufvurätt. Han hade emellertid blifvit medveten om sin egentliga kallelse, och den skandinaviska konstutställningen i Stockholm 1850 samt en resa till Düsseldorf 1851 stadgade hans beslut att på allvar egna sig åt målarkonsten. 1852 började han sina studier vid konstakademien, hvilken 1853 belönade hans Landskap, motiv från Göta älf, med kungliga medaljen. 1854 begaf han sig åter till Düsseldorf, där han studerade under Gude, reste 1855 öfver Paris till Genève, där han nyttjade Calames undervisning, och tillbragte sedan ett år, 1856–57, i Rom, där han målade och utställde ett större arbete, Utsikt af passet öfver Simplon, som såldes till England. Hemkommen hösten 1857, började han att kostnadsfritt meddela akademiens elever undervisning i landskapsmålning, hvilket blef uppslaget till akademiens landskapsskola. Han blef 1861 vice och 1867 ordinarie professor i landskapsmålning. 1869 gjorde han en längre studieresa i Norge. Vid 1862 års världsutställning i London och 1872 års skandinaviska utställning i Köpenhamn var han kommissarie för den svenska konstafdelningen. – B:s tidigare landskap visa stark påverkan af Achenbach, Gude och Calame. Ett eget uttryckssätt arbetade han sig till under studiet af den svenska naturen. “Hans lynne kom honom att välja just de stämningar, som hans landsmän voro mest förtrogna med och som de helst sågo afbildade. Han blef björkhagarnas och insjösträndernas målare, sommarhimlens och middagssolens, de betande kornas och de hvita molnens. Han sökte mindre det majestätiska i naturen än dess blida leende eller dess stilla ensamhet” (G. Nordensvan). Bland hans målningar äro motiven från Mälarens stränder många, och han tröttnade ej att upprepa dem – äfven från Bohus läns fisklägen, från Skåne och från Norge målade han kustbilder och fjällmotiv i lugn och i storm. Hans landskap äro med omsorg och skicklighet komponerade och solidt målade med smidig och elegant pensel. De beteckna ett betydelsefullt led i den svenska landskapskonstens utveckling. Nationalmuseum eger tre af B:s målningar: Utsikt i Uri i Schweiz (1858), Skogslandskap med vattenfall i Småland (1862) och I barrskogen (1868), sex finnas i Göteborgs museum, Under björkarna (1870) i Köpenhamns konstmuseum och Björkskog (1876) i Kristiania nationalgalleri. Många af hans målningar såldes till utlandet, och vid flera utställningar hemma och utrikes erhöll han utmärkelser, bl. a. i Paris 1867 och Wien 1873. B. dog i Stockholm 23 sept. 1880.

Nordisk Familjebok, “Uggleupplagan” 1904-26

Fjord 30 Weekender, Early to Mid-1970s

Almedalen

Jag var ganska många gånger på Gotland när jag var liten, och även några gånger senare, men det var mycket länge sedan sist. Många fina minnen gör att jag länge har velat återvända. Förra veckan insåg jag plötsligt att det nu finns ett nytt gott skäl att göra det.

Den så kallade Almedalsveckan har tidigare inte intresserat mig i någon större utsträckning. Men nu när SD har en egen dag och deltar i många fler debatter, seminarier och intervjuer är situationen en annan. Även några av de seminarier Axess arrangerade var i år viktiga, inte minst det i vilket Tino Sanandaji medverkade, om integrationspolitikens tillkortakommanden. Oklara historiska och politisk-filosofiska punkter fanns i det Sanandaji framförde, men det ska bli intressant att se om eller i vilken utsträckning Axess och närstående personer visar sig mottagliga för hans mer allmänna perspektiv.

Även seminariet om den nya “Blue Labour”-strömningen med Marc Steirs och Maurice Glasman var av central betydelse och angav en väg som även den svenska socialdemokratin nu kunde slå in på. Man påminner sig att det även finns “Red Tories”. Blue Labour och Red Tories låter som om de tillsammans skulle kunna utvecklas till den rätta föreningen: den sociala konservatismen eller konservativa socialismen.

Slutligen får nämnas seminariet om konservatism och liberalism, där Johan Norbergs och Carl Rudbecks typ av vänsterlibertarianism, här representerad av den signifikativt nog till Miljöpartiet övergångne Mattias Svensson, nu slutligen även för de mindre initierade måste ha framstått som just så kuriös och extrem som den i själva verket alltid varit. D.v.s. alltifrån 90-talet då den i så stor utsträckning trängde ut de värdefulla kulturkonservativa tendenserna bland annat på Timbro. Nu tycks den i alla fall vara på väg att avlägsnas från den centrala och seriösa borgerliga idédebatten sådan den förs i Axess-lägret. Johan Tralaus konservatism intar förhoppningsvis dess plats. En skilsmässa mellan konservatismen och denna typ av liberalism är, förklarades det i ljuset av Svenssons agerande gentemot Per Gudmundsson, nödvändig.

Gudmundson, vars behandling från vänsterns sida upptog en stor del av detta sistnämnda seminarium, upprepar dock i Svenska Dagbladet något förvånande den enkla mediala kategoriseringen av SD:s politik i termer av “missnöje” och “populism“. Rent förbluffande är att han finner jämförelserna med Per Albin Hansson i Åkessons tal vara en “exempellös fräckhet”. Detta tal, som introducerar en länge saknad dimension av idéinnehåll och vision i svensk politisk debatt och får fram en klar och distinkt åskådningsmässig profil, saknade också enligt Gudmundson konkreta programpunkter. Trots att mängder av sådana passerade revy genom hela talet, i Åkessons sammanfattningar av vad SD redan åstadkommit och försökt åstadkomma i riksdagen, nämner Gudmundson den skärpta kriminalpolitiken som den enda. Samtidigt förbiser han att vad det just på den punkten handlade om främst var en ansträngning från Åkesson att få bort den felaktiga bilden av SD som enfrågeparti.

Det är svårt att se varför denne ledarskribent som visat viss självständighet – bland annat just nu i Almedalen – ägnar sig åt denna typ av simplistisk propaganda. Hur kan han, som utan tvekan kan bättre, finna det meningsfullt att anpassa sig till denna nivå? Hans partiella sanningssägande har ju gjort att vi kommit att vänta oss mycket mer av honom, trots begränsningarna och ohållbarheterna i hans och Svenska Dagbladets politiska åskådning i övrigt.

Han tvingar också med detta ledarstick återigen på oss frågan om dagens tidningars meningsfullhet överhuvudtaget. Hur mycket längre kommer välutbildade läsare vilja fortsätta betala för att läsa texter av denna typ, när de har tillgång till i alla avseenden överlägsen politisk kommentar, analys och diskussion på internätet?

Att de elementära teoretiska och historiska definitionerna och distinktionerna rörande fenomenet populism här och överallt i svenska media idag lyser med sin frånvaro avspeglar inte bara en anmärkningsvärd okunnighet och tankemässig tomhet i allmänhet. Beteckningen populism är visserligen ett framsteg i jämförelse med de beteckningar man tidigare försökte avfärda SD med. Men även denna saknar redan trovärdighet. Den tunnhet och ytlighet som allena kan förklara den utsträckning i vilken SD:s motståndare nu förlitar sig på användningen av termen populism antyder också något som liknar en kris av hjälplöshet i hela den bakomliggande, ständigt nyimproviserade politiska strategi i vars genomförande Gudmundsons tidning är en del.

Och vari bestod fräckheten i Åkessons jämförelser med Hansson? Menar Gudmundsson att det är principiellt fel att åberopa och överta en idé från ett annat parti som övergivit eller som man anser övergivit den? Vad ska man i så fall säga om Moderaterna, som genom hela sin historia präglats – och inte minst idag präglas – av åberopande och övertagande av idéer från andra partier utan att dessa övergivit dem?

Som Gudmundsson mycket väl vet är det i detta fall, folkhemmet, fråga om en idé som hade en bred förankring och som först formulerades inte av socialdemokraterna utan, med dess egna tonvikter, av högern – den gamla höger som ibland ville och försökte se och faktiskt ofta också såg till hela folkets och nationens väl – men från vars förverkligande man redan under Lindman började fjärma sig. Det är med andra ord en idé som redan övertagits från ett parti av ett annat.

Var det fräckt av Hansson? Knappast. Bortom den betydelseförskjutning som ägde rum i övertagandet, vittnar detta också om den självklara samsyn i värnandet av Sverige som på den tiden ibland präglade partierna från höger till vänster, och som dagens sjuklöver för länge sedan ersatt med en samsyn i nedvärderingen och förnekandet av Sverige. Inte ens alla kommunistiska internationalister delade denna nya ståndpunkt på Hanssons tid. Man frågar sig om Gudmundson menar att även den socialt ansvarskännande högern och socialdemokratin var populistiska missnöjespartier.

Åkesson gör helt enkelt detsamma som Hansson: Han tar över termen och idén. Men även nu ges den nya betydelsemässiga tonvikter, och delvis återknyts till den höger från vilken Hansson först tog över den. Åkesson presenterar den i linje med den klassiska socialkonservatismen, hänvisar explicit till denna form av konservatism. Han anknyter till ett äldre, för de stora partierna i mycket gemensamt synsätt där det nationella inslaget i SD:s politik var en självklarhet.

Det finns ingenting märkvärdigt här och definitivt inte någonting fräckt. Gudmundsons kritik hade varit obegriplig även om den inte uttryckts i ordalag så häpnadsväckande starka att vi mot vår vilja måste ifrågasätta hans omdöme.

Åkessons tal:

Blogginläggs längd

Bloggposten är fortfarande ett relativt nytt format för publikation, och det finns mycket nytt och viktigt som sägs om det. Ämnet, bloggar och blogginlägg som sådana, borde i själva verket tematiseras i separata inlägg också här.

Det bör vara viktigt för allt fler, i takt med att bloggarnas eller de personliga hemsidornas betydelse i allmänhet växer och hela den publicistiska världen förändras av detta och av internätet i allmänhet. Och för mig är det viktigt inte minst eftersom den här bloggen av olika skäl har kommit att bli en mer betydelsefull del av min tillvaro än jag förutsåg när jag startade den.

Här ska jag nu bara kort säga något om bloggposters längd. Kritik har nämligen flera gånger framförts mot att mina inlägg är för långa.

Något bör dock kanske först också sägas om orden ”inlägg” och ”post” (eller ”blogginlägg” och ”bloggpost”) som jag använder omväxlingsvis. En språkvårdsdiskussion kunde föras om båda. ”Inlägg” är, tycker jag, inte någon helt självklar motsvarighet till det engelska ”post”. Det implicerar att allt som ”postas” i bloggar – och detta har ju inte några begränsningar – är delar av pågående debatt. Detta är i och för sig inte någon ointressant föreställning; kanske är den till och med värdefull och filosofisk: Livet och universum som en enda stor, oavslutad och oavslutbar dialog. Men ordet känns ibland ändå ofta något för krångligt och speciellt. ”Post”, å andra sidan, är väl även på engelska i denna mening också en neologism och ej helt okontroversiell. Men både ”post” och verbet ”posta” tycks ha blivit så etablerade nya anglicismer att de är svåra att undvika. Och de är egentligen ganska bra i blogg- och forumsammanhang.

Det finns en mängd akademiker inom nya discipliner som studerar informationsteknologins inflytande på kulturens former och deras förändringar ur olika perspektiv, inklusive historiska. Vad jag främst är intresserad av är teknologins potential för förnyelse och spridning av kulturtraditionens essentiella värden och insikter, såväl som av dess traditionella former.

Dess radikala förändringskapacitet i sig, som sådan, kan inte utan urskillning bejakas, i synnerhet inte när den kopplas till gamla eller nya och mer eller mindre direkta versioner av i sak historiematerialistisk teori, och i deterministiska termer förklaras en gång för alla förändra kulturen som blott överbyggnad. Självfallet finns här stora och komplexa frågor om hur kulturen påverkas och hur den inte påverkas, frågor som jag inte kan gå in på nu. Det är tillräckligt att betona att det teknologiska framsteget alltid har ägt en kulturell förnyelsepotential jag ser som motsatt den reduktivt materialistiska förståelsen av teknologins historiska betydelse, och att detta också är en potential som alltid i betydande utsträckning aktualiserats, om än blott parallellt med vad som ofta på olika sätt är problematiska, ibland rent destruktiva potentialer.

Relationen mellan teknologin och kulturella formers förändring blir tydlig när vi ser hur frågan om blogginläggs längd hänger samman med frågan om blogginläggs genre. Det är möjligt att betrakta bloggposten som en egen, ny litterär genre, framvuxen i gränslandet mellan en rad olika äldre, och närmast dagboksanteckningen, artikeln, essän. Men det är ibland också möjligt att se den som blott en ny teknisk form för publicering av texter i flera av de äldre genrerna. Och en fråga som inställer sig är om dessa genrer som kan publiceras på detta nya sätt inskränker sig till de ur vilka bloggposten närmast framvuxit.

Jag är medveten om att det för det mesta har kommit att tillhöra denna nya form att inläggen är korta, och att det förväntas att de ska vara det. Men finns det, vill jag fråga, någon principiell nödvändighet att det ska vara på det sättet? Vad hindrar att man publicerar exempelvis längre akademiska uppsatser i bloggar? Än så länge är det väl bara de tidigare opublicerade kapitelutkasten om ‘Bowne’s Idealistic Personalism’ som är rent akademiska texter i den här bloggen. Men jag ser alltså inget hinder att publicera fler. Och vad hindrar att man rentav publicerar texter av böckers längd, förslagsvis kapitel för kapitel?

Gör man det, bör man väl lämpligen blanda de längre texterna med kortare. I den här bloggen har jag ju också varvat textinlägg med konst och videoklipp, de senare med såväl musik som annat. Jag ser sådana poster som lika viktiga som de egna texterna – inte minst konsten och musiken, som jag egentligen borde ägna mer tid att kommentera. Gjorde jag det, skulle ju dessa inlägg visserligen också bli textinlägg, men bilden eller videon skulle ändå erbjuda visuell variation. Så länge jag inte kommenterar dem gör de ju det i än högre grad. En blogg med enbart större eller mindre textmassor kan väl se litet enformig ut, och i synnerhet finns det ju inget skäl att den ska göra det när dess syfte i lika hög grad som att förmedla egna texter är att lyfta fram och kommunicera medels viss konst och musik (samtliga bloggens temata, eller Categories, hänger också på ett bestämt sätt nära samman, som jag förklarat på About-sidan).

De som inte vill läsa de längre textposterna kan ju lätt hoppa över dem, och hålla sig bara till de korta. De längre inläggen är sådana som lämpligen trycks ut och tas med tillbaka till fåtöljhörnan och tekoppen, eller kanske tåget eller flyget. Jag råkar veta att jag har läsare som gör just det. Men man bör då känna till att jag hittills under de närmaste timmarna, dagarna, ibland veckorna efter att jag publicerat ett inlägg, hittat fel och svagheter som jag under denna tid rättat och avhjälpt. De läsare som efter denna tid återvänt till mina inlägg, eller först då upptäckt dem, har i samtliga fall funnit långt bättre versioner!

Värdet av att skriva kort och koncist är uppenbart. Faktiskt har jag ju också gjort det i åtminstone några fall här, och jag hoppas kunna fortsätta med det. Men det är ett värde som är genre- och kontextspecifikt och inte generaliserbart. Det är svårt för mig att se några problem med att också använda bloggen för andra genrer, syften och sammanhang som är lika viktiga och nödvändiga.

Det finns alltså mycket mer att säga om detta och angränsande ämnen, och naturligtvis också litteratur och forskning ägnad dem som säkert i någon utsträckning borde uppmärksammas. Synpunkter är välkomna.