Rupert Sheldrake: The Science Delusion

Freeing the Spirit of Enquiry

Coronet, 2012 Amazon.co.uk

Book Description:

The science delusion is the belief that science already understands the nature of reality. The fundamental questions are answered, leaving only the details to be filled in. In this book, Dr Rupert Sheldrake, one of the world’s most innovative scientists, shows that science is being constricted by assumptions that have hardened into dogmas. The ‘scientific worldview’ has become a belief system. All reality is material or physical. The world is a machine, made up of dead matter. Nature is purposeless. Consciousness is nothing but the physical activity of the brain. Free will is an illusion. God exists only as an idea in human minds, imprisoned within our skulls.

The science delusion is the belief that science already understands the nature of reality. The fundamental questions are answered, leaving only the details to be filled in. In this book, Dr Rupert Sheldrake, one of the world’s most innovative scientists, shows that science is being constricted by assumptions that have hardened into dogmas. The ‘scientific worldview’ has become a belief system. All reality is material or physical. The world is a machine, made up of dead matter. Nature is purposeless. Consciousness is nothing but the physical activity of the brain. Free will is an illusion. God exists only as an idea in human minds, imprisoned within our skulls.

Sheldrake examines these dogmas scientifically, and shows persuasively that science would be better off without them: freer, more interesting, and more fun.

About the Author:

Dr Rupert Sheldrake is a biologist and author of more than 80 technical papers and 10 books, including A New Science of Life. He was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, where he was Director of Studies in cell biology, and was also a Research Fellow of the Royal Society. From 2005-2010 he was the Director of the Perrott-Warrick Project for research on unexplained human abilities, funded from Trinity College, Cambridge. He is currently a Fellow of the Institute of Noetic Sciences in California, and a Visiting Professor at the Graduate Institute in Connecticut. He is married, has two sons and lives in London. His web site is www.sheldrake.org.

JOB’s Comment:

I cannot judge about Sheldrake’s controversial work in biochemistry. But in this book in particular he clearly raises, as a scientist, decisive philosophical questions, and that is important.

Stefan Huster & Karsten Rudolph, Hg.: Vom Rechtsstaat zum Präventionsstaat

Suhrkamp, 2008

Ob Bundestrojaner oder Internetverbot für Terrorverdächtige: Seit dem 11. September wissen wir, wie schwierig es ist, das Verhältnis von Freiheit und Sicherheit in der Balance zu halten. Lebt Schäuble Orwellsche Überwachungsphantasien aus? Sind seine Gegner naiv? Wie weit darf der Staat gehen, um seine Bürger zu schützen? Diese Fragen diskutieren in diesem Band unter anderem Gerhart Baum und Burkhard Hirsch, die erfolgreich gegen den Abschuß von Passagiermaschinen klagten, der ehemalige BND-Chef August Hanning, Wolfgang Bosbach, der stellvertretende Vorsitzende der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion, und der Terrorismusexperte Ulrich Schneckener.

Über die Herausgeber:

Stefan Huster ist Professor für Öffentliches Recht an der Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Karsten Rudolph lehrt dort Geschichtswissenschaft und ist stellvertretender Vorsitzender der nordrhein-westfälischen SPD.

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 2

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 1

I will assume here a general understanding on the part of my readers of the origins of humanism and humanistic thought in classical antiquity, which I have discussed at length elsewhere, and where we find basic positions and values wich I presuppose in all discussions of humanism in the strict sense in which I use the term. These original formulations of course already imply several central positions of classical idealism or of idealism in the broad sense, which I have also often discussed as fundamental to my general understanding of humanism, and which for this reason will also be left our here.

Instead, I will focus on what are still less obvious and well-known aspects of the relation between humanism and the broader idealistic tradition. In line with the version of traditionalism I find defensible, to a considerable extent the ethical insights, the metaphysical background, and the theological dimension which makes true humanism in essential respects, in the Western tradition, a Christian humanism, must in my view be accepted. Christianity in itself of course also contributed strongly to Western humanism.

But again, as confirmed even by, for instance, the so-called “transcendental Thomists”, who, as Thomists, are not in my main Platonic line of idealism in the broader sense, some insights of modern idealism, rightly understood, have the capacity to enrich, broaden, and in very important respects modify the scholastic tradition. Properly understood and more thoroughly assimilated, I think it even has in itself the capacity and the resources to recapture precisely the historically still accessible truths and values which in the past it tended to lose.

For the purpose of the definition of humanistic philosophy, the esoteric tradition needs to be mentioned again, since it has been a constitutive ingredient in much modern Western humanism, ever since the Renaissance, and has contributed to the epochal self-understanding of Western modernity as such. Esotericism is connected with the whole of the long-standing tradition of non-scientistic philosophy which, going back, through historicism, idealism, romanticism, and Vico to the Renaissance, is central to what we mean today by humanistic philosophy. There is in this line what has been called a “mystical humanism” which, as almost always in the traditions of Western esotericism, is metaphysically and morally ambiguous, and which has left a correspondingly ambiguous legacy.

On the one hand, through its view of the nature of God in relation to the world and man, and, increasingly, to history, it has contributed to the secularization of the Christian eschaton and to the deification of man, in whom alone God is seen to become real – and thence, through the swift transformations in the work of the Left Hegelians, the Saint-Simonians and others, to a purely secular humanism representing one of the meanings of the word humanistic and indeed idealistic philosophy which, in accordance with the historical alignment I have signalled, I reject outright.

On the other hand, esotericism, which has been described as a third, major intellectual current in the West, occupying a position between rationalistic science and faith or revealed religion, stands in connection with some of the most interesting positions in several periods of the history of Western philosophy. In the modern period, most importantly, there developed gradually in this tradition an understanding of the meaning and role of the imagination which had been absent or rudimentary in classical and mediaeval thought. This esoteric development was more closely related to Kant’s Copernican revolution, the post-Kantian idealists, and the romantics than has hitherto been understood, and it resulted in new insights into the nature and function of the imagination as creative. The new understanding of the active mind and its production of imaginative synthetic wholes had decisive and far-reaching implications for epistemology which are still far from generally understood.

This is one essential insight of humanistic philosophy in the sense I have in mind – and more generally a central part of the neo-humanistic thought of nineteenth-century Germany which came to define much of humanism in Europe and the West – which needs to be salvaged from the morass of the pantheistic revolution. Although the mutual criticism produced by the surface clashes of the latter’s rationalistic and romantic wings hides their underlying interdependence and even reciprocal reinforcement (not only is Oakeshott right that irrationalism is often rationalism in disguise, but of course the converse is equally true), it also displays partial truths which could be admitted even by the critic who seeks to rise beyond the whole of their vast and complex dialectic and their powerful historical momentum, and to return to a more strictly defined humanism in the classical and Christian traditions.

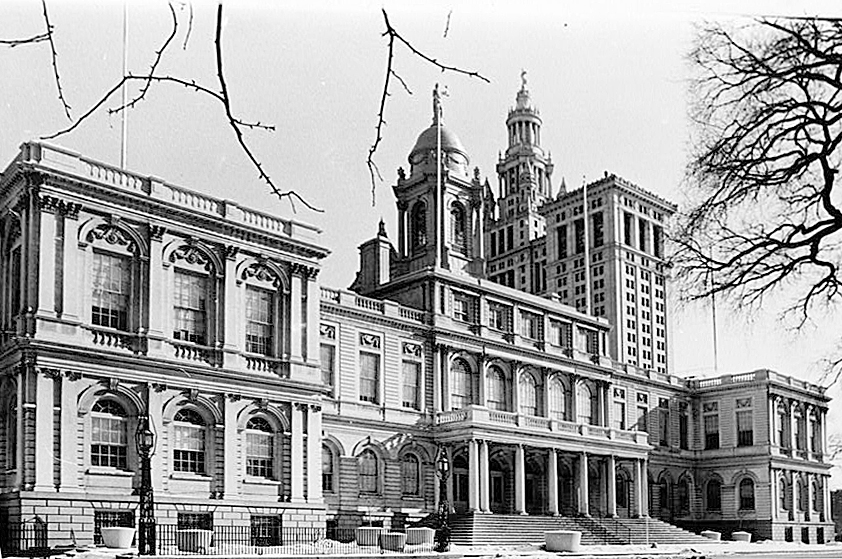

Joseph-François Mangin & John McComb, Jr: New York City Hall

Bonaventura

Den exoteriska kyrkoorganisationens religion anammades som moralisk-disciplinär statlig tvångsordning av det sig redan splittrande och upplösande romerska imperiet, och detta kunde inte hindra dess fall. Men kyrkreligionens ordning och dess lära överlevde och övertogs av medeltidens feodalism. Bibelns exoterism i allmänhet och den kristna dogmatikens i synnerhet blev de medel genom vilket hela det framväxande västerlandet alltifrån början hölls nere i den Skapade Människovaron, och i förståelsen av den i termer av dess Synd och målet att endast Frihalsas från denna genom Försanthållande av Trosbekännelsen. De kvarvarande spåren av platonism i den fulla, vidare meningen, av högre gnosis, esoterism, mystik och österländskt inflytande som gick utöver denna trånga horisont förföljdes, utplånades, drevs under jorden, eller tolererades som bäst i strikt reglerade, begränsade och övervakade former. Pseudo-Dionysios övade ett – kontrollerat och underordnat – inflytande endast så länge hans identitet missförstods som ovedersägligt kanonisk-auktoritativ.

Detta, i lika hög grad som någon materialism, ateism och empirisk-vetenskaplig världsåskådning, är den historisk-kulturellt-ideologiska grundorsaken till att den överväldigande majoriteten av västerländska människor än idag lever i nästan total andligt-existentiell blindhet och inte förstår de mest grundläggande sanningarna om livet och världen och den andliga verkligheten. Men på ett allmänt plan är denna religiösa exoterism ändå i sig en produkt av samma faktorer som alstrar materialismen, ateismen och vetenskapen som världsåskådning: den fundamentala slutenheten i den mänskliga, psykofysiska apparatens ego, den självförståelse som följer ur denna identifikation, och de basala samhälleliga, moraliska och kulturella förhållanden och nödvändigheter som den ger upphov till.

Teologin formas per definition av allt detta. Under högmedeltiden finner vi en rad tänkare som i olika proportioner blandar augustinskt och aristoteliskt inflytande i sina föreställningar om själen och personen. Även Thomas av Aquino förenar i allmänhet dessa inflytanden, men knappast företrädesvis i dessa frågor. Få uppnår väl Augustinus’ position, men vissa förmår bättre relatera hans insikter till personkategorin. Frågorna om själen och personen är olika men nära relaterade. Framför allt finns p.g.a. den exoteriska dogmatiken en ständig spänning mellan vad jag beskrivit som själspersonen och kroppspersonen. Men eftersom verkligheten är vad den är, alldeles oavsett vad den egoidentifierade Människan och den världsliga makt hon utövar vill, var det givetvis aldrig möjligt att helt utsläcka den högre andliga varsevaron och insikten om dess sanning. Även detta faktum framglimtar ibland som tankenödvändigheter i teologins dunkla och hopplösa härva av andligt och kroppsligt.

Att konstatera allt detta är inte detsamma som att förneka kristendomens relativa och partiella historiska förtjänster, alltifrån början, på fromhetens, dygdens, moralens och humanitetens kulturella nivå, och ofta inte ens ifråga om “tron”, förstådd som det teistiska försanthållandet, i en mycket allmän mening.

Bonaventura ifrågasätter materian som ensam individuationsprincip, och hävdar istället att individualiteten, discretio individualis, uppkommer ur formens och materians förening och ömsesidiga appropriation. Personligheten, discretio personalis, uppkommer när materian förenas med en rationell form, och när i substansen den rationella naturen äger actualis eminentia, d.v.s. inte har någon högre natur över sig. Därför är människans mänskliga förnuftiga natur personkonstituerande, till skillnad från Sonens mänskliga förnuftiga natur. [Copleston, A History of Philosophy, II (1950), 273.]

Bonaventura är lärjunge till Alexander av Hales och utgår från användningen av ordet person om bärare och innehavare av värdigheter. Men han skiljer sig i det han använder det principiellt om alla människor, oavsett förvärvade egenskaper, eftersom de alla delar den förnuftiga natur som i sig är en sådan värdighet. Här är således den förnuftiga naturen tillräcklig.

Människan tycks dock också förklaras ha en enhetlig, odödlig själ (inom den ortodoxa kristendomen kan detta förstås bara betyda en skapad själ, inte en evig) som består inte bara av den rationella fakulteten utan också av den sinnliga. Detta är något vi känner igen från vissa platonister. Själen är också både form och materia i aristotelisk mening, men båda dessa sägs vara av andlig natur, varigenom dess enhet, avskild från allt “materiellt-materiellt”, bevaras, och själen dessutom är självindividuerande. Trots denna platonska dualism är själen och kroppen karaktäristiskt nog “naturligt” förbundna med varandra och skall vid uppståndelsen återförenas. [Ibid. 278 ff.] Trots själens platonska självständighet, och fastän personskapet konstitueras genom den formens rationella natur som hör själen till (även om själen inte uteslutande är rationell) och personskapet därför härrör ur själen, innefattar därför persondefinitionen också kroppen.

Så långt framstår det hela som jämförelsevis klart och begripligt. Men tyvärr ger det inte en fullständig bild av Bonaventuras position. Till persondefinitionen hör enligt honom en enhetlig, partikulär, singulär och med andra substanser icke förenlig substans, en fullständig, i sig själv förankrad helhet. Men den andligt-materiella, samtidigt förnuftiga och sinnliga själen är något mer än den rationella form som utgör personkonstituerande princip, och den personsubstanen ska i själva verket i likhet med den icke-personliga individualiteten vara individuell endast i och genom föreningen med den vanliga, “materiellt-materiella” materien.

Vi befinner oss redan mitt i den framväxande skolastisk-filosofiska gröten. Men eftersom det som gäller för form-materie-relationen i allmänhet ju torde gälla också för den “rent andliga” form-materie-relation som utgör själen, och eftersom själen därmed är självindividuerande, borde ju dock indirekt följa att om formelementet också i själen är rationellt, vilket det väl inte finns någon anledning att betvivla, själen i sig är en individuell person. Därmed skulle det ändå, trots den skolastiska åtskillnaden mellan själs- och personfrågorna, såvitt jag förstår också för Bonaventura helt enkelt vara själen som förlänar människan inte bara ett allmänt utan ett individuellt personskap.

Att Bonaventura likafullt förnekar detta på grund av kroppens och själens naturliga förening, är utomordentligt signifikativt. Inte heller skolastikens användning av Aristoteles framstår som självklart framgångsrik. Den kristna ortodoxins människosyn förblir i detta centrala avseende oförenlig med platonismen o.s.v., och förhållandet mellan själspersonligheten och kroppspersonligheten blir konstitutivt oklart – i bästa fall endast ogenomträngligt komplext, i värsta fall direkt motsägelsefullt.

William McGregor Paxton: In the Studio

Bengt Göransson: Tankar om politik

Om boken:

Det politiska språket förändras. Begrepp försvinner, andra nyskapas och inte sällan innebär det dramatiska förändringar i politikens innehåll. Med erfarenhet och skärpa skärskådar förre skol- och kulturminister Bengt Göransson samtidens politiska tendenser i ett medialt klimat som ställer allt högre krav på både politiker och medborgare.

Ur förordet:

“Som kritisk betraktare känner jag mig fri. Jag är ingen doktor, den som vet precis hur hela samhället ska organiseras. Jag är fortsatt starkt kritisk mot personer och grupper som har den totala och slutliga lösningen i beredskap. De undertecknar hellre en ärorik reservation än stöder en möjlig kompromiss. Jag hoppas att en eller annan gång kunna förmå den som har att fatta beslut att tänka en stund till och att nyansera beslutet. Det är farligt om beslutspotens får ersätta tankeverksamhet. Tänkandet – och det egna skrivandet – är förutsättningen för varje ledarskap. I själva verket tror jag att just det oberoende i förhållande till beslutsapparaterna som jag haft under snart tjugo år har givit mig tillgång till en större arena än jag annars skulle ha haft. Jag kan säga och skriva vad jag vill eftersom ingen behöver bry sig om det!”

Född 1932, socialdemokratisk skol- och kulturminister 1982–89 och utbildningsminister 1989–91, är numera verksam som engagerad folkbildare och samhällsdebattör. År 2010 innehar han gästprofessuren till Torgny Segerstedts minne vid Göteborgs universitet.

JOB:s kommentar:

Den svenska arbetarrörelsen och socialdemokratin har ett rikt arv, som inte alltid förvaltas på rätt sätt efter att partiet under senare årtionden alltmer underordnat sig nyliberalismen och globalkapitalismen. Vi finner det exempelvis i dess folkbildningssträvanden, i kooperationen, i den grundläggande internationalismen, som ursprungligen bröt med en inskränkt nationalism inom borgerligheten och i sig åter blir av central betydelse i dagens läge, även om den delvis och periodvis kommit att ges en politiskt problematisk substans. Göransson är en god representant för mycket av det bästa i socialdemokratins tradition.

Richard M. Weaver: The Ethics of Rhetoric

Literary Licensing, 2011 (1953) Amazon.com

Blurb:

Weaver’s Ethics of Rhetoric, originally published in 1953, has been called his most important statement on the ethical and cultural role of rhetoric. A strong advocate of cultural conservatism, Weaver (1910-1953) argued strongly for the role of liberal studies in the face of what he saw as the encroachments of modern scientific and technological forces in society. He was particularly opposed to sociology. In rhetoric he drew many of his ideas from Plato, especially his Phaedrus. As a result, all the main strands of Weaver’s thought can be seen in this volume, beginning with his essay on the Phaedrus and proceeding through his discussion of evolution in the 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial.” In addition, this book includes studies of Lincoln, Burke, and Milton, and remarks about sociology and some proposals for modern rhetoric. Each essay poses issues still under discussion today.

Weaver’s Ethics of Rhetoric, originally published in 1953, has been called his most important statement on the ethical and cultural role of rhetoric. A strong advocate of cultural conservatism, Weaver (1910-1953) argued strongly for the role of liberal studies in the face of what he saw as the encroachments of modern scientific and technological forces in society. He was particularly opposed to sociology. In rhetoric he drew many of his ideas from Plato, especially his Phaedrus. As a result, all the main strands of Weaver’s thought can be seen in this volume, beginning with his essay on the Phaedrus and proceeding through his discussion of evolution in the 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial.” In addition, this book includes studies of Lincoln, Burke, and Milton, and remarks about sociology and some proposals for modern rhetoric. Each essay poses issues still under discussion today. An Open, Intelligible, and Semiotic Universe

Keith Ward on Materialism, 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Ward continues his explanation of the terms: “The universe is open, because the principle of indeterminacy rules out the possibility of precise prediction of the future. It establishes probability as more fundamental than definite determinism, and sees the future as open to many creative possibilities, rather than as predestined to run along unavoidable tram-lines.” This is so regardless of how we understand the mathematical structure of contemporary physics. Determinism is no longer supported by physics, the openness of the universe means that freedom is, from its perspective, possible. This of course has many implications, and speaks in favour of personalism especially. I feel no strong need to add anything further to this point at the moment.

“The universe is emergent, in that it develops new properties – like conscious awareness or intentional action – that are not wholly explicable in terms of prior physical states, though such properties seem to develop in natural ways from previous physical states.” This is how it seems from the perspective of science. But given the description of the current state of physics, it is of course not particularly clear what a “physical state” is.

“The universe is intelligible and mathematically beautiful to a degree that could not have been envisaged even a hundred years ago. As Eugene Wigner has said, it is an unexpected gift that the mathematical structure of the universe should be as elegant and rationally comprehensible as it is.” This seems to imply the Platonic understanding of the mathematical structure. “Finally, the universe is semiotic, in that it does not simply rearrange its basic elements in different combinations. Many of those combinations are semiotic – they carry information. DNA molecules, for example, carry the codes for arranging proteins to build organic bodies. And perhaps the basic laws of the universe are computational, coding instructions for assembling new structures. As Paul Davies and John Gribbin put it, ‘In place of clod-like particles of matter in a lumbering Newtonian machine we have an interlocking network of information exchange – a holistic, indeterministic and open system – vibrant with potentialities and bestowed with infinite richness.'”

I am not sure how common this usage of “semiotic” is. But the passage is perhaps as clear as at present it can be with regard to “information exchange” as far as this can be understood from the particular perspective of science. At the same time it of course cries out for the supplementation of philosophical reflection even for a basic understanding of its real meaning. Of course, Ward will soon provide precisely this.

“If this is materialism, it is materialism in a new key. The physical basis of the universe seems to have an inner propensity towards information-processing and retrieval, that is, towards intelligent consciousness.” The “physical basis” seems by now to be a problematic postulate, a misleading conceptual residue. But “materialism in a new key”, insofar as it is the position of physics qua physics, is not intended here to be understood as in itself tantamount to idealism. The account shows only that classical materialism is regarded as obsolete in physics.

Ken Wilber writes in the preface to his important anthology Quantum Questions: Mystical Writings of the World’s Great Physicists (1984): “The theme of this book, if I may briefly summarize the argument of the physicists presented herein, is that modern physics offers no positive support (let alone proof) for a mystical worldview. Nevertheless, every one of the physicists in this volume was a mystic. They simply believed, to a man, that if modern physics no longer objects to a religious worldview, it offers no positive support either; properly speaking, it is indifferent to all that. The very compelling reasons why these pioneering physicists did not believe that physics and mysticism shared similar worldviews, and the very compelling reasons that they nevertheless all became mystics – just that is the dual theme of this anthology. If they did not get their mysticism from a study of modern physics, where did they get it? And why?”

I think a major part of the answer to these questions is simply: philosophy. It should of course be noted that idealistic philosophy does not necessarily involve mysticism. But mysticism could be regarded not only as something more that is not covered by such philosophy, but also as something that is in principle accounted for but not necessarily in itself explored by it. It is significant that Wilber, and the physicists whose texts he collects – Heisenberg, Schroedinger, Einstein, De Broglie, Jeans, Planck, Pauli, and Eddington – do in fact speak in terms of mysticism. Yet it seems the reason they became mystics is not just their new physics itself, and also not just mystic experience, but inevitable philosophical reflection as partly but not entirely separable either from science or mysticism.

For the real idealist conclusion, philosophy must be added to contemporary physics. But the same was the case with classical materialism. The classical materialism of physics itself necessarily involved a degree of philosophical reflection, as does the current conclusion regarding its obsolescence. With the recognition of these facts, with the help of philosophy, as well as of philosophy’s general unavoidability, it is of course quite possible that physics will be more generally pursued (as it already seems to be by some) on the basis of a philosophical affirmation of idealism, as in the past it was implicitly or explicitly based on the philosophical presuppositions of classical materialism.

But the support science lends to the case for idealism remains incomplete, as Ward is aware, although it does go beyond the mere negative sub-case against materialism. My concern is the truth of idealism in itself, as philosophy. As I have explained, the part of the case for it that makes reference to science or physics and their relation to materialism is included here, in the form of this commentary on Ward, merely for the sake of the kind of completeness of the representation of idealism that might rightly be expected.