Category: Idealism

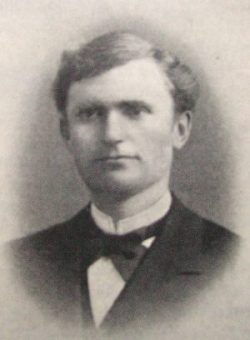

P. J. H. Leander

Per Johan Herman Leander (1831-1907) efterträdde 1886 Nyblaeus som professor i praktisk filosofi i Lund. Bland hans verk återfinns Om substansbegreppet hos Cartesius, Spinoza och Leibnitz (1862), Om substansbegreppet hos Kant och de tänkare som från honom utgått (1863), Något om den samtida filosofien i Tyskland, Danmark och Frankrike (1876), Boströms lära om Guds idéer (1886), och det postumt utgivna Idélära från Boströms filosofiska ståndpunkt (1910).

Ingen artikel om Leander finns ens i första upplagan av Alf Ahlbergs filosofiska lexikon, vars artiklar jag återgivit i tidigare inlägg om svenska filosofer. Därför citerar jag här i stället några stycken ur Svante Nordins Den Boströmska skolan och den svenska idealismens fall från 1981 (s. 77-80):

Ingen artikel om Leander finns ens i första upplagan av Alf Ahlbergs filosofiska lexikon, vars artiklar jag återgivit i tidigare inlägg om svenska filosofer. Därför citerar jag här i stället några stycken ur Svante Nordins Den Boströmska skolan och den svenska idealismens fall från 1981 (s. 77-80):

–

Leanders magnum opus är…hans Boströms lära om Guds idéer (1886). Detta arbete innehåller bl.a. en utförlig granskning av striden mellan Nyblaeus och Edfeldt. I fråga om det problem som denna tvist behandlade, övergången från det oändliga till det ändliga, hade Leander kommit att medge att det fanns en lucka i Boströms system. Hans ställningstagande till de båda antagonisterna blir salomoniskt, på ett sätt som påminner om Wikners. Leander håller med Edfeldt att enligt Boström Guds idéer “äro oändliga såsom bestämningar” samtidigt som han ger Nyblaeus rätt i att de “såsom väsen äfven omedelbart i och för Gud måste tänkas såsom ändliga”.

En sådan lösning visar hän mot att det finns svårigheter i Boströms system, något som Leander också erkänner. På en punkt, och därtill en av de väsentligaste, framträder han nämligen öppet som revisionist: han förnekar Boströms lära om “idéernas materiella [d.v.s. såsom konkreta individer tänkta] ofullkomlighet” eller om “talserien”.

Enligt Leander strider uppfattningen om en “talserie” mot läran om mångfald i enhet. Den senare innebär att det absoluta ingår i allt och förlänar enhet åt detta. Läran om talserien eller idéernas materiella ofullkomlighet innebär däremot, om den genomförs konsekvent, att det absoluta endast negativt bestämmer de lägre idéerna och att det på så vis är den lägsta idén, inte den högsta, som ingår i alla andra. – Talet 1 ingår i talet 100, men talet 100 ingår inte i talet 1!

Leander finner det obegripligt hur en lägre idé utifrån Boströms förutsättningar kan sägas hänvisa till en högre eller till det hela. Tar man på allvar förutsättningen att en högre idé endast innehåller de lägre blir det omöjligt att förstå hur detta dess innehåll kan “hänvisa” till några högre idéer än den själv. Konsekvensen av detta blir särskilt betänklig i avseende på den högsta idén, det absoluta. Hur kan man nämligen veta att denna idé är den högsta? Utifrån den själv kan man ju inte veta något om detta eftersom ingen idé innehåller annat än lägre idéer.

Kanske kan man visualisera Leanders tankegång genom att föreställa sig de i talserien inordnade idéerna som ett antal personer vilka står i en rad med ansiktena vända åt samma håll. Nr ett i raden kan då inte se någon av de övriga. Nr två kan enbart se nr ett, nr tre enbart nr ett och nr två o.s.v. Ingen kan se dem som står bakom honom själv i raden och ingen kan därför veta sig vara den siste. Den siste kan förvandlas till den näst siste utan att hans perceptionsfält förändras genom att ytterligare en person kommer och ställer sig bakom. Egenskapen att kunna se alla de övriga blir på så vis en yttre, kontingent egenskap. Leander finner det stötande och orimligt att på detta sätt reducera den absoluta idén till bara den sista i en rad eller det högsta numret i en serie.

Boströms lära om Guds idéer innehöll en rad kritiska argument men inte något positivt alternativ. De som…intresserade sig för saken fick vänta på ett sådant i nära 25 år. Då utgav Liljeqvist postumt ett manuskript av Leander som denne varit sysselsatt med under sina sista år.

I detta manuskript Idélära från Boströms filosofiska ståndpunkt (1910) börjar Leander med att betrakta det hela som system i anknytning till Sahlins lära om tänkandets grundformer. Utgångspunkten är då, att systematiskhet, d.v.s. logiskt sammanhang och motsägelsefrihet, är förutsättningen för allt tänkande och all kunskap om verkligheten. Tänkt som system erbjuder helhetens förhållande till sina delar inga större svårigheter. Varje del har det hela som logisk förutsättning. Därmed finns också det hela givet i varje del.

Att enbart tänka sig helheten som system, d.v.s. ur formell synpunkt, är emellertid enligt Leander inte tillräckligt. Uppfattningen av idéerna som subjekt eller personer kan nämligen aldrig härledas ur systemets begrepp. Helheten måste vara en viss sorts system, närmare bestämt en organism. Om helheten (Gud) således ur reell synpunkt fattas som organism ställer sig problemet om dess förhållande till delarna som ett problem om organismens förhållande till sina organ. Detta förhållande tänker sig Leander på ett sätt som innebär en modifikation, men en pietetsfull modifikation, av Boströms ståndpunkt.

Organen måste till att börja med vara fullt bestämda av det hela. Till varandra står de i relation bara via det hela. Men den relation, vari organen via helheten står till varandra, innebär att Boströms lära om talserien upprättas, fastän i ny tappning. Organen antas nämligen innehålla det hela i olika grad, och eftersom det helas innehåll utgörs just av organen, måste då dessa även innehålla varandra i olika grad. Med Leanders egen, något tungfotade formulering: “då de själfva utgöra allt innehåll hos det hela och intet finnes utom detta, är sådant möjligt endast därigenom, att det ena af hvilka två som helst innehåller det andra utan att själft i detta innehållas, hvilket åter i fråga om idéerna med deras omedelbara betydelse af former af enheten och dennas betydelse af att i och för sig vara det hela innebär, att den ena af hvilka två som helst utan att själf innehållas i den andra genom enheten innehåller denna uti sig”.

Här har således läran om idéernas materiella ofullkomlighet, d.v.s. talserien, kommit tillbaka genom fönstret. Skillnaden mot Boström är bara att idéerna nu sägs innehålla varandra endast genom helheten. Vördnaden för Boström är naturligtvis en drivkraft bakom denna restauration. En annan är den funktion som den materiella ofullkomligheten har hos denne, nämligen att underlätta förklaringen av det relativa ur det absoluta. En brevväxling mellan Leander och den än mer rättrogne Keijser kastar ljus över detta, liksom över Leanders förhållande till Sahlin. Keijser har ifrågasatt huruvida Sahlin verkligen förbättrat Boströms lära genom att förneka all motsats hos det absoluta…Leander svarar med att framhålla, att det är när systemet fattas formellt, inte när det fattas reellt, som motsats saknas hos Gud. Denna skillnad hade Boström inte insett:

“Därför anser jag att det är en stor förtjenst af Sahlin att hafva häfdat systemets begrepp såsom innebärande fullkomlig samstämmighet. Felet hos Sahlin är, att han utsträcker denna samstämmighet äfven till organismens begrepp eller från idéerna såsom organer hos Gud aflägsnar all motsats i betydelsen af uteslutning, hvarigenom han gör det omöjligt att komma öfver från det oändliga till det ändliga.”

Leander vill med andra ord slingra sig ur problemet med enhet kontra mångfald genom att göra en skillnad mellan helheten fattad som system, som logiskt motsägelsefritt sammanhang, och helheten fattad som organism. Eftersom den reella organismen ändå på något sätt skall vara identisk med det formella logiska systemet, blir det aldrig fullt klart hur detta innebär en lösning.

Leanders förbättring att låta den lägre idén endast i och genom enheten ingå i den högre erbjöd honom en annan fördel, som han lade stor vikt vid. Gud kunde nu i stället för som det högsta talet i talserien fattas som dennas enhet och själv vara höjd över all kvantitativ bestämning. Därmed undveks den olyckliga konsekvensen av talserieanalogin att Gud s.a.s. bara av en tillfällighet var det högsta talet.

Leander illustrerar själv sin modifiering av Boström genom att säga, att hos honom Gud inte är högsta talet, t. ex. 1000, i talserien, utan själva begreppet tal. “Och enheten i detta är icke talet 1 (ett) utan själfva begreppet tal. Talet 1 är blott det lägsta momentet eller den lägsta idén. Alla tal äro idéer, talet själft enheten och det hela. I alla talen ingår begreppet tal och är så enheten i dem. Men det förutsättes nu äfven vara enhet af dem och så utgöra det egentliga hela eller systemet själft såsom enhet i och af mångfald.”

Leanders sista arbete kan ses som ett gott exempel på skolastik inom filosofin. Om Boström, som Nyblaeus framhållit, i grund och botten var en intuitiv filosof, så ledde hans på intuitiv väg tillkomna filosofi dock till svårigheter av logisk art. Till stor del blev det hans lärjungars sak att försöka reda ut dessa. Därvid invecklade de sig i alltmera komplicerade konstruktioner. Det intuitiva momentet blev svårare och svårare att fasthålla.

Boströmianismens motståndare tog också med förkärlek fasta på draget av ofruktbart hårklyveri. Anhängarna kunde å andra sidan försvara sig med att ett mått av begreppsexercis är nödvändig i varje filosofi, eftersom varje helhetsuppfattning måste ge upphov till sina tekniska problem. Om sunda förnuftet undgår sådana problem beror det enbart på att sunda förnuftet saknar filosofisk helhetsuppfattning.

Idealism as Alternative Modernity, 4

Idealism as Alternative Modernity, 1

Idealism as Alternative Modernity, 2

Idealism as Alternative Modernity, 3

I was in fact alerted to the problems – not least the moral ones – of the pantheistic revolution not primarily by Christian orthodoxy, but by that form of idealism that in the “empire of idealism” was called personal idealism and that in one version dominated Swedish philosophy in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and, later, by the creatively renewed classicist criticism of the American new humanist Irving Babbitt and two of his Swedish philosophical successors who were not disinclined, as he himself was, to connect his ideas with idealism, in the footsteps of no less an idealist than Benedetto Croce.

If we consider the problematically revolutionary aspect, Christianity too, of course, as well as Judaism, have in their own ways, and mainly through their ever newly interpretable eschatologies, contributed quite as much to it. But, building also partly on the work of Eric Voegelin and some Christian historians (Voegelin was not an orthodox Christian) I also accept that traditional Christian orthodoxy does have valid general points to adduce against the pantheistic revolution, although they are not exclusively its own contribution. They are primarily the ones relating to transcendence, the general nature of the order of the world, freedom, moral responsibility, and individual personality. Through the emphasis on them, it has provided a needed counterbalance.

But broader idealism itself, properly conceived, is not identical with or reducible to the pantheistic revolution that generated problematic modernity. That it is not per definition revolutionary in the immanentizing metaphysical and moral sense I discussed in Greece is obvious, to the point of supporting almost an opposite understanding of it, when we consider the various historical implications and applications of Platonism, and, a fortiori, the social structures supported by Eastern idealisms.

This of course highlights the problems with bracketing the vast differences between modern and other forms of idealism, but, as some of the mentioned idealism critics are of course well aware, modern idealism too often manifested explicitly non-revolutionary forms, and already in Hegel. Moreover, the tension between the conservative and the radical versions is also clearly discernible throughout the history of Western esotericism.

Alongside the often closely related esotericism, idealism represents the long neglected third main avenue of Western thought, distinct from both fundamentalist religion and modern materialist or nihilist secularism. Rightly conceived, it provides in itself many of the resources of the requisite alternative modernity, not least with regard to the metaphysical, moral, and political dimensions of the question of the relation between the individual and the larger wholes which was a central theme in my Greece paper.

And in so-called personal idealism or idealistic personalism in its most advanced forms, the correctives with regard to the mentioned valid points of criticism, and indeed some further and no less important points, are, as I always suggest, already available, independently of the mythological peculiarities of Christian dogmatics and even to a considerable extent independently of general Christian theology.

The main weakness of nineteenth-century absolute idealism from this position is not that it is absolute, but that it is not fully idealistic. With this I reiterate my in-house idealistic challenge with which some of you are by now familiar. For all the important partial truths I defended at Oxford, Bernard Bosanquet’s position that “consistent realism and absolute idealism differ in name only” epitomizes for me the philosophical confusion and error of the pantheistic revolution of the modernity to which an alternative is needed.

The optimal resources for the formulation of the idealist contribution to an alternative modernity therefore seem to me to be those of personal idealism or personal absolute idealism in its most advanced forms. And as I always point out – both because of the way in which I myself became an idealist and for the sake of corroborating my argument for the universality of these issues – there are from the beginning, despite, or beyond, the obvious difficulties of translation and interpretation, striking similarities with the Western debates between absolute and personal idealists in the Vedanta tradition in the East.

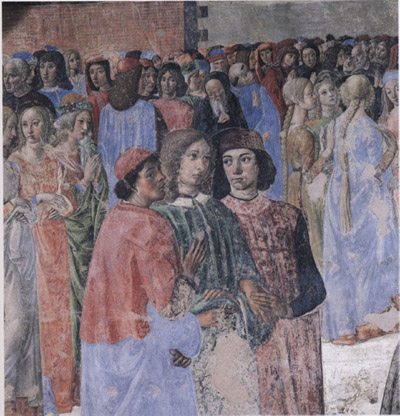

Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, Poliziano

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 4

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 1

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 2

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 3

The basic idealistic insight regarding what could be called the experiential whole can be traced back to the first beginnings not only of idealism in Germany, but of the new aesthetic ideas of romanticism in a broad sense. This insight is common to the more “complete” idealism I seek to defend, which synthesizes the Platonic tradition with the partial truths of modern idealism, and the latter form of idealism in itself. It is well described by Folke Leander and Claes G. Ryn in their selective defence of idealism as part of their so-called value-centered historicism. Here as elsewhere, I will build partly on their account. But I will relate it to the work of a wider range of idealist thinkers, draw out its implications of a more complete absolute idealism, and indicate briefly the difference made by the distinct positions of personal idealism or personal absolute idealism.

The discovery of wholes, inspired by the new view of the active and synthetic imagination, was decisive for the reaction against the sensationalistic materialism of the Enlightenment and its dissolution of experience into impressions and associations, and had implications for the whole field of humanistic knowledge and thought.

The post-Kantians and the romantics, perceiving the absence in Kant of a critique of his own critical reason, moved on from his abstractly and rationalistically conceived synthetic wholes to discover, along with the properly creative imagination, the primacy of real, concrete, non-conceptual experiential wholes – moral, aesthetic, and philosophical. Coleridge’s concern was the transcendental deduction of the imagination, i. e. to show that it is a necessary part of the categorical network that constitutes the mind. This imagination orders our experiential wholes and the symbols of the infinity in which everything experienced exists and from which it is separated only by the abstractive operations of reason in the sense that the Germans, less felicitously, designated by the term Verstand and Coleridge, equally unfelicitously, the Understanding.

The insights were now fully expressed that there are no atomic “facts” related only externally to each other, that facts have whatever meaning and reality they have only because of the relations within experiential wholes, that everything is to be understood in terms of its essential relatedness, and that ultimately there is meaning only in relation to the largest whole. The idealist understanding of experience, distinct from both rationalism and empiricism, was soon fully elaborated. Everything has to start from the direct experiential awareness of the flow of life, unmediated by formulas and laws, a flow which is more fundamental and real than any of the conditional modes of experience, as Oakeshott calls them.

I should add here that the expression “flow of life”, used by Leander and Ryn, does not for me signify an endorsement of those expressions of the “philosophy of life”, from romanticism to Dilthey and beyond, which rejected idealism as mere “school philosophy” and sought something else beyond it. Indeed, I find this to be a shared error of the philosophical currents of phenomenology, existentialism and hermeneutics. Although the case is not as serious as that of the analytic philosophers, their rejection of idealism still seems to me often superficial and stereotypical, not seldom based on sheer misunderstanding and spatio-temporally parochial, incomplete assimilation. The work of the philosophers in these traditions contain important insights, but they need to be reconnected to a properly understood and reformulated idealism. The broad metaphysical horizons opened up by the renewed idealist tradition in the nineteenth century, with their great potential not least in the field of comparative studies, need to be restored.

Such an idealism includes but also transcends the insights formulated by Leander and Ryn. Supplemented or qualified by the insights of degrees of reality, truth, and value, and of the perspectival relativity and the possibility of error that follow from a clear distinction between the finite and the infinite subjects of the kind insisted on by the personal idealists, it seems to me that to assert with a more complete idealism that reality is identical with experience, that appearances are real, not illusions, and that experience is self-authenticating, not guraranteed by anything more fundamental, since there is nothing more fundamental, might be admissible. To be real is to be in experience, and every experience is part of or content of consciousness. And the full understanding of what this implies makes it clear that it is not at all a matter of a subjectivist imperialism or reduction of the being of things.

Ultimate reality, on this view, is experience as a whole, the ordered sum of appearances or of what exists, or the experience of this totality – which we can of course conceive of only imperfectly – in which all partial perspectives are overcome. This is one aspect of the absolute. The absolute, the ultimate reality, is absolute experience. Truth is this reality itself, the whole of reality or the absolute. We can in a sense understand that this is so although our own experience as finite is only partial and relative. The absolute is the ultimate standard of truth, reality, and value. Truth is in this perspective ontological rather than semantic, and not only a property of propositions or judgements. These are always distinct from the whole and partial, they are, in their own way, true as partaking of the authority of the whole.

Human thought progresses by stages or moments in its understanding of reality, although Hegel, the Hermeticist, is mistaken in his suggestion that it can actually reach a final completion of self-realization in the Idea, the point at which, in complete knowledge, it grasps its true identity with the Whole. He is right that, to the extent that and in the cases where progress takes place, each successive moment, though defective, contains a greater measure of truth than its predecessor, that each stage represents a provisional coherence until reason, exposing its inchoateness, ascends to the next platform of understanding in an evolutionary hierarchy, and that in relation to the absolute the stages differ in degree rather than kind. There are, generally speaking, degrees of abstraction and mutilation, an ascending scale of validity.

Hans Forssell

Svante Nordins avsnitt om Hans Forssell (1843-1901) i Den Boströmska skolan och den svenska idealismens fall ger kanske en något överdriven bild av Forssells boströmianism, i det att den helt förbigår både de allmänna spänningarna mellan liberalismen och boströmianismen som kvarstod även efter att Boströms närmaste efterföljare börjat revidera statsläran, och den tidige Forssells egen kritik. Men avsnittet visar i alla fall att boströmianism och liberalism på visst sätt kunde förenas vid denna tid, och Forssell blev väl mer konservativ med tiden. Avsnittet återfinns på s. 43:

“Hans Forssell var något av oscarianskt underbarn. En man med mångsidiga intellektuella intressen gjorde han viktiga insatser särskilt på den ekonomiska historiens område. Föga mer än 30 år gammal blev han finansminister i De Geers andra ministär. Till sin politiska åskådning framstod han, särskilt under senare delen av sitt liv, som konservativ. Han deltog energiskt i kampen mot materialism, positivism och naturalism. 1881 uppträdde Forssell så för att förhindra kommunala bidrag till Anton Nyströms arbetarinstitut. Som ledarskribent i Stockholms Dagblad bekämpade han Strindberg, Verdandi och andra samhället upplösande kulturkrafter.

“Hans Forssell var något av oscarianskt underbarn. En man med mångsidiga intellektuella intressen gjorde han viktiga insatser särskilt på den ekonomiska historiens område. Föga mer än 30 år gammal blev han finansminister i De Geers andra ministär. Till sin politiska åskådning framstod han, särskilt under senare delen av sitt liv, som konservativ. Han deltog energiskt i kampen mot materialism, positivism och naturalism. 1881 uppträdde Forssell så för att förhindra kommunala bidrag till Anton Nyströms arbetarinstitut. Som ledarskribent i Stockholms Dagblad bekämpade han Strindberg, Verdandi och andra samhället upplösande kulturkrafter.

Forssell tillhörde Boströms personliga lärjungar, men graden av hans Boströmtrohet har bedömts olika. Torgny Segerstedt har hävdat att det inte torde ‘råda något tvivel om att han själv räknade sig som boströmian’. Mot detta har Nils Elvander gjort gällande att ‘Forssells inställning till den boströmska filosofien var…från början självständig och kritisk’.

Det finns ingen anledning att gå djupare in på detta spörsmål. Det räcker med att Forssell allmänt framstod som en av boströmianismens allierade. 1875 rycker han t.ex. ut till försvar för Boström gentemot Waldemar Dons i en anmälan i Svensk Tidskrift av norrmannens Boströmkritik. Inom det boströmska lägret förefaller man ha varit utomordentligt nöjd med hans insats. Sahlin sade sig t.ex. inte ha ‘ett ord att ändra eller tillägga’ i det Forssell skrivit.

Till andra talanger var Forssell en ypperlig stilist och en man med kulturella intressen. Han hedrades också vederbörligen med en plats i Svenska akademin.”

Idealism as Alternative Modernity, 3

Idealism as Alternative Modernity, 1

Idealism as Alternative Modernity, 2

While the continuity of its Schellingian and Hegelian versions with the esoteric tradition is today obvious, and other continuities stressed by Muirhead and others are certainly not unimportant, modern idealism in the German post-Kantian and the Anglo-American line is often, perhaps even generally, of a different kind, and introduced new and other elements. In my paper at the Idealism Today conference at Oxford in 2005, ’Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy’, I defended what I find to be the general truths in those lines of idealism. When I speak of idealism as alternative modernity, I have in mind primarily those truths, but I am strongly inclined to emphasize a need for a broader concept of idealism for this purpose too, an idealism reinforced, as it were, by the ”Berkeleyan”, esoteric, Platonic, and Vedantic elements that were decisive for my own early intellectual formation.

In most of those forms, idealism represents, and ever since antiquity in the case of some of them, an alternative to certain historically context-specific exoteric developments of Christian orthodoxy. Because of this, it often tended to become intrinsically and constitutively a part modernity, and both its rationalist, scientific, Enlightenment variation and its romantic one (as I have defined those terms in several publications). Scholars sometimes rightly focus on Hegelianism in the context of the question of the so-called legitimacy of modernity, but their interpretations of both Hegelianism and modernity for the most part seem, as in the case of Robert Pippin, unduly reductive. What is at stake, I suggest, is in reality much broader metaphysical and spiritual concerns.

Although it is perhaps partly because of my ”reinforced” idealism that I have never been able to see the various attempted refutations of idealism in the twentieth century as even very noteworthy, let alone convincing, I insist, as in my Oxford paper, that there are central insights of modern, specifically German idealism and its variations in the Anglo-American “empire of idealism” which are still very much valid, relevant, and indeed simply true, and not just of historical interest. The historical scholarship that dominates the presentations at these conferences help transmit that legacy even as most participants are not themselves thoroughgoing idealists, as it were.

Anglo-American idealism scholars long tended, and quite naturally, to focus on the attack of the analytical philosophers, and to a much lesser extent on the attack of phenomenologists, existentialists, and neo-Thomists. But no less important, I think, is to take a closer look at the efforts of, by now, generations of liberal political philosophers and Marxist historians of various stripes to try to isolate an admissible idealist prehistory of their own liberalism and Marxism and dismiss other important elements of idealism as exclusively part and parcel of the German so-called Sonderweg. Many of the latter elements, as characteristically analysed in works such as Fritz Ringer’s influential The Decline of the German Mandarins, entered into Anglo-American idealism too, even as the latter significantly modified them in accordance with the differences in their cultural traditions and mentalities. Much greater discernment is required for the understanding of idealism – in all its worldview ramifications, not just in philosophy but for the understanding of culture, history, politics, and religion – in Germany and in other European countries.

This is so not least in view of the factual historical course taken by modernity. Did idealism in my broader sense produce the modernity that, in time, turned against it? In my paper at the International Conference on Anglo-American Idealism in Pyrgos, Greece, in 2003, I explored this problem, and argued that, largely because of the opposition to the mentioned developments of Christian exotericism, the broader idealism (before the specific modern versions were developed) often turned into what I called a ”pantheistic revolution” which, because of its inner dynamic, generated the problematically one-sided versions of rationalism and romanticism which have come to determine the shape and substance of the main form of modernity.

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 3

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 1

Idealism and the Renewal of Humanistic Philosophy, 2

Scientism was thus correctly criticized by philosophical currents deeply shaped by romanticism, even when as alternatives these were not in themselves tenable due to the problems precisely with this romanticism. The analytic philosophy which turned against and replaced idealism was a militantly scientistic philosophy, and still tries, even if only awkwardly, to be so. Much of romantically inspired “continental” philosophy was sometimes correctly criticized by analytic philosophers even as their alternative was not in itself tenable either, due to the problems with its scientism. But primarily because of the latter problems, the sharp demarcation line between analytic and continental philosophy has for a long time and in many respects been blurred.

This is not always because analytic philosophers relinquished their scientism and continental philosophers their romanticism. Again, on a deeper analysis, we have to do with two expressions of the same underlying cultural dynamic, and thus there were, not surprisingly, instances if not of the potential of synthesis, at least of a characteristic combination. But to the extent that such relinquishing of untenable elements – whether because of the criticism from the other side taking effect or for other reasons – was the reason why the line was blurred, the blurring was welcome.

Some philosophers call for further mutual modification of the analytic and continental traditions. The former has to recognize and assimilate the central humanistic, historical, and hermeneutic concerns of the latter, while the latter is held to stand in need of the formal and conceptual clarity and rigour of the former. It is difficult to see how anything like this is possible without discarding completely the scientistic substance of the analytic project. But to the extent that an interpenetration of the two traditions leads to a mutual modification which does involve this, it is certainly of the greatest historical and intellectual significance. That continental philosophy was not always what the analytic philosophers said it was has always been obvious, and that analytic philosophy can be disconnected as a set of formal instruments from its scientistic substance has of course also long been clear, and is exemplified today not least by analytic philosophical theology and “analytical Thomism”.

Idealistic philosophy was part of a whole cultural paradigm in many countries, which, in the eyes of the radical critics, shaped by the incipient general, post-World War I twentieth-century sensibilities, often made its positions wrongly appear conservative and almost “traditional” in my sense, constituting as it did one major expression of the Victorian spirit, its moralism, and its aesthetics, and symbolizing much of the world before the rise of high modernism and the general cultural radicalism shared, for all of their differences, by the logical positivists, Bloomsbury, the Marxists, the Freudians, and many others. Idealism seemed to represent the lost world of the nineteenth century. Defending it in the Britain of Lytton Stratchey required new and different talents. Defending it in terms of that Britain, or as to some significant extent part of it, was from the beginning a project of poor prospects.

Yet in some more and less obvious ways, nineteenth-century idealism did in fact live on. There were idealists here and there, and idealism’s nineteenth-century legacy contributed important elements to the work of the few non-analytic or, possibly, non-scientistic analytic philosophers in Britain and America, and even more to continental philosophy. Typically, however, idealism was conspicuously absent from the analytic-continental controversy. Both camps considered themselves “post-idealist”. Under the influence of, for instance, Heidegger’s criticism of the epistemology of neo-Kantianism, historicism, and earlier forms of hermeneutics in the case of continental philosophy, and, again, simply of scientism in the case of analytic philosophy, both long tended to forget or play down the idealist themes of modern philosophy of history, art, action, science, and language.

Today, the contributions of idealism in these areas, and elsewhere, are becoming more visible. Not least for the purpose of a modified reconstruction of the “subject”, including but also transcending epistemology, continental philosophers more consciously take up greater or smaller elements of idealism, often with a thorough historical knowledge of its traditions, but also sometimes without critical discernment, and adding some of the problematic twentieth-century assumptions. Some philosophers at least trained in the analytic tradition take up various idealist positions, but, it seems, often from outside, as it were, without the full idealist understanding of experience, reason, or the role of philosophy. It is time, I think, to pay attention not only to the scattered idealist themes and positions that appear here and there in contemporary philosophy, and to not only rediscover idealism’s contributions to and influence on later and other philosophies, but to renew something of the more integral vision of idealism. In the respects mentioned here, the twentieth century is over.

As selectively reappropriated, idealism could, I suggest, contribute both to the completion of the mutually modifying interpenetration of the analytic and continental traditions as I have outlined it, and, simultaneously, to the process of transcending them both. For when some misunderstandings in the criticism of idealism have been cleared up, it might be possible to see that idealism can supplement and indeed in the most central respects supplant both, not least through a broader and deeper view of reason and of objective truth which, for different reasons and with different but equally characteristic consequences, they have both lost.

As disentangled from the pantheistic revolution, idealism is a badly needed moderating force in secular modernity which, I contend, should be embraced in its unabridged anti-naturalistic and anti-physicalist import. The need is for a non-reductive spiritualism.

Michael Oakeshott: Experience and Its Modes

Cambridge University Press, 1986 (1933) Amazon.com

Book Description:

This classic work is here published for the first time in paperback in recognition of its enduring importance. Its theme is Modality: human experience recognized as a variety of independent, self-consistent worlds of discourse, each the invention of human intelligence, but each also to be understood as abstract and an arrest in human experience. The theme is pursued in a consideration of the practical, the historical and the scientific modes of understanding.

This classic work is here published for the first time in paperback in recognition of its enduring importance. Its theme is Modality: human experience recognized as a variety of independent, self-consistent worlds of discourse, each the invention of human intelligence, but each also to be understood as abstract and an arrest in human experience. The theme is pursued in a consideration of the practical, the historical and the scientific modes of understanding.Daniel Klockhoff

[Daniel] K., estetiker och skald, f. 14 sept. 1840 å Ytterstfors brukspredikant-boställe i Västerbotten, d. 29 juli 1867 i Uppsala, blef student i Uppsala 1859, filos. kandidat 1863, filos. doktor 1866 och s. å. docent i estetik vid nämnda universitet. Hängifven lärjunge af filosofen Boström, tillegnade K. sig under själfständigt tankearbete dennes spekulativa resultat och gjorde anmärkningsvärda förarbeten till att i den rationella idealismen skaffa den estetiska vetenskapen en fastare grundval, än panteismen förmått lägga. I denna syftning skref han sin gradualdisputation Om den pantheistiska esthetiken (1864) och afh. Om det tragiska (1865). Bland bidrag till de första årgångarna af den 1865 uppsatta “Svensk litteraturtidskrift” märkas artikeln Om dödsstraffet, som vill bevisa detta straffs orättmätighet, samt en del granskningar af teologisk litteratur, i hvilka han på en gång kraftigt och hofsamt för filosofiens och den protestantisk-religiösa utvecklingens talan. Som skald uppträdde K. först inom det 1860 i Uppsala stiftade förbundet N. S. (“Namnlösa sällskapet”) och offentliggjorde under signaturen “K.” lyriska dikter i kalendrarna “Isblomman” (1861) samt “Sånger och berättelser” (1863 och 1865). Hans dikter äro fina och innerliga uttryck för en kysk erotisk känsla och ett nobelt sinnelag.

[Daniel] K., estetiker och skald, f. 14 sept. 1840 å Ytterstfors brukspredikant-boställe i Västerbotten, d. 29 juli 1867 i Uppsala, blef student i Uppsala 1859, filos. kandidat 1863, filos. doktor 1866 och s. å. docent i estetik vid nämnda universitet. Hängifven lärjunge af filosofen Boström, tillegnade K. sig under själfständigt tankearbete dennes spekulativa resultat och gjorde anmärkningsvärda förarbeten till att i den rationella idealismen skaffa den estetiska vetenskapen en fastare grundval, än panteismen förmått lägga. I denna syftning skref han sin gradualdisputation Om den pantheistiska esthetiken (1864) och afh. Om det tragiska (1865). Bland bidrag till de första årgångarna af den 1865 uppsatta “Svensk litteraturtidskrift” märkas artikeln Om dödsstraffet, som vill bevisa detta straffs orättmätighet, samt en del granskningar af teologisk litteratur, i hvilka han på en gång kraftigt och hofsamt för filosofiens och den protestantisk-religiösa utvecklingens talan. Som skald uppträdde K. först inom det 1860 i Uppsala stiftade förbundet N. S. (“Namnlösa sällskapet”) och offentliggjorde under signaturen “K.” lyriska dikter i kalendrarna “Isblomman” (1861) samt “Sånger och berättelser” (1863 och 1865). Hans dikter äro fina och innerliga uttryck för en kysk erotisk känsla och ett nobelt sinnelag.

K:s Efterlemnade skrifter utgåfvos 1871 (med inledning af C. D. af Wirsén); s. å. utkommo Dikter särskildt.

Ugglan

Ur Gösta Lundströms artikel i Svenskt biografiskt lexikon:

K. härstammade från en norrländsk prästsläkt o. fick en lärd uppfostran, först av fadern, sedan i läroverk. Efter gymnasieåren i Härnösand undervisades han privat av C. J. Dahlbäck, då docent i filosofi, ett ämne som blev K:s huvudstudium sedan han 1859 blivit student i Uppsala. Det var främst estetikens problem som fängslade honom. Han blev lärjunge till C. J. Boström, vars idealistiska tankebyggnad på kristen grund kom K:s personliga åskådning nära. Detta uteslöt dock inte en viss självständighet, bl.a. politikens område, där K. var mer reformvänlig än lärofadern.

K:s gradualavhandling Om den pantheistiska esthetiken 64 innebar ett försök att på den boströmska “rationella” filosofins grund med analytisk metod kritiskt granska Hegels o. Vischers panteistiska skönhetslära. Den följande år utgivna avhandlingen Om det tragiska avsåg att definiera detta estetiska begrepp o. ge en rationell förklaring på personlighetsfilosofins grund. Skriften meriterade K. till docentur i estetik. Han ansågs som en betydande spekulativ begåvning, o. vid univ. fästes stora förhoppningar vid honom, men på grund av hans tidiga bortgång kom hans filosofiska forskning att stanna vid ansatser…

En värdefull insats gjorde K. för den av C. R. Nyblom redigerade Sv. litteratur-tidskrift. I en programartikel visade han en för tiden vidsynt blick för en kulturtidskrifts uppgifter; målet skulle vara “en högre fantasiodling” i nationell anda. Han medarbetade flitigt i tidskriften, bl.a. med inlägg i religionsfilosofiska frågor, varvid han försvarade filosofins frihet o avvisade teologiska angrepp på denna vetenskap.